When Presses Show Their Age

November 1, 2013Comments

...metal stampers can repair/rebuild, or replace with new. Depending on the customer base, type of work and quality requirements, a diligent diagnose-and-repair program may suffice. In other cases, the benefits of new press technology allows stampers to take on new, more tightly toleranced and complex stampings.

|

| A Verson gap-frame press undergoes backshaft repair at Charles Richter Corp., courtesy of Field Service Mechanical Co. |

Numerous geriatric mechanical presses still pound a at metal stampers coast to coast, only requiring their owners to diligently inspect, diagnose and repair to keep them running like new, or close to it. As long as the customer requirements for part quality and complexity don’t change much, why buy new?

That’s been the recipe for success at Charles Richter Corp., Wallkill, NY. For more than 100 years, the metal stamper has served a variety of customers—most in the lighting industry—with deep-drawn and stamped parts using some 100 presses. Most are mechanical OBI models, with a handful of pneumatic and transfer presses thrown into the mix. Their nameplates are those that stamping historians recall fondly—Bliss, Verson, Federal, Warco etc.

Company President David Richter can’t think of any reason to buy new, when his maintenance manager has troubleshooting and repair work well in hand. And if repairs get too intense he has a local, trusted source of repair and rebuild services in Field Service Mechanical Co. (FSM), Bohemia, NY.

At the opposite end of the spectrum we find Choice Fabricators, Inc. (CFI), a second-generation privately held metalforming company in Rainbow City, AL, where owner and president David Chadwick is in the midst of an aggressive pressroom-overhaul program. His newly expanded 200,000-sq.-ft. pressroom (the overall plant encompasses 335,000 sq. ft.) houses 14 automatic mechanical presses. The firm is one of the beneficiaries of the efforts of a large appliance OEM to reshore much of its stampings.

|

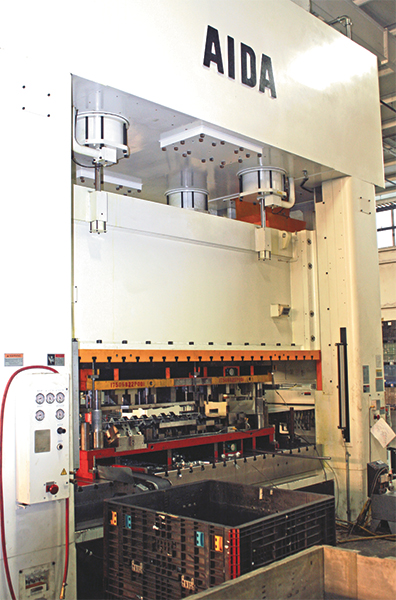

| One of the newest presses at Choice Fabricators is this Aida 660-ton link-drive model, purchased in 2012. It tackles the firm’s most challenging work—complex parts that have difficult draw or coining operations. |

Three of CFI’s presses are less than 2 yr. old, and Chadwick (as of this writing) has been negotiating the purchase of four additional new presses to be completed by 2016. These will replace what Chadwick refers to as aging presses—vintage 2000 or so.

Backshaft, Bearing Repairs and More

Charles Richter’s presses range from a pair of 5-ton Blisses with 7.5-in. shut height to a 275-ton Bliss SE-2 with 48- by 84-in. bed and 15.5-in. shut height. The 50,000-sq.-ft. shop is divided into three pressrooms—one for heavier drawing operations, one for secondary operations and the third for small-part stamping. Once home to 70 employees, the offshoring of stampings to China beginning in 2005 has left the company with some 20 employees. And of its inventory of 100 or so presses, about 12 are running at any one time, says David Richter.“We have the luxury of matching the right press to each and every job,” he says, “thanks to a vast range of bed sizes, tonnage ratings and shut heights.” The firm has some 150 active customers and 500 active dies, from an inventory numbered in the thousands. Draw capacity is 10 in. on a 17-in.-dia. blank.

Richter’s presses stay busy drawing and stamping primarily steel from 24 to 14 gauge. Draw/first-operation presses run coil stock; its seven transfer presses typically run five to nine die stations. When we spoke with Richter, two of the 12 presses in action were transfers.

Richter is not concerned with new-press features like improved rigidity and accuracy. Part dimensional tolerances, he says, are ±5 to 10 percent, and “I would never overload a press,” he adds, “so adding rigidity by adding gussets or beefing up a crown or bed is not something we would do. We have enough capacity with the presses already here to meet customer requirements, especially since we keep the presses in perfect working condition.”

Such attention to press maintenance and repair has Richter periodically repairing or replacing crankshafts—“we have, in a few instances, replaced crankshafts to add 2 in. or so to a press’s stroke, to increase draw-depth capacity,” Richter says. It also has, in several instances, replaced mechanical clutches with air clutches, to improve safety. Other common repairs, typically performed by FSM, include backshaft repair, ram and gib machining, repair of slide-adjustment mechanisms, counterbalance and cushion repair and rebuild and lubrication-system repair.

|

| This 2008-vintage Aida 1100-ton transfer press is a workhorse for Choice Fabricators, so much so that the company expects to purchase an even larger transfer press in the next year or two. Its Noble transfer system swings out of the to allow a quick 15-min. changeover for progressive-die work. |

“We’ve had FSM in here probably 10 times in the last 10 years,” Richter says. “Most recently, they performed a complete backshaft rebuild on a Bliss gap-frame press. They had the press back up and running in 3 weeks.”

Expansion, on the Backs of Bigger, Better Presses

At CFI, reshoring of appliance work that began in 2010 led to a 35-percent uptick in work. That rush of orders caused the company’s pressroom to go, in 90 days, from having 25-percent excess capacity to being 15 percent undercapacity. To keep up, the firm, which also counts automotive and HVAC OEMs as customers, added two new Aida presses (a 660-ton link-drive press bought in 2012 and a 300-ton standard mechanical bought in 2013) to its stable, as well as a 440-ton Seyi press also added in 2012.

“The acquisition of those three presses, as well as an 1100-ton Aida transfer presses purchased in 2008,” says Chadwick, “represents the beginning phases of our expansion. Now we’re in a strategic-planning phase for the future, and expect to purchase another four presses by 2016—maybe even a servo. Three of these will replace older presses, and the fourth will be a larger transfer press, since the 1100-ton transfer is maxed out.

“Five years ago, a 144-in.-bed press was considered big,” Chadwick continues. “Now we don’t have anything on our books less than 240 in. left to right, and the new transfer press we’re looking at purchasing soon (1250 to 1500 ton) will have a 320-in. bed. Parts are bigger, but we also need to use more stations in the dies to satisfy part-complexity challenges.”

New and Improved

What’s the “improved” part of the “new and improved” press promise? When it comes to mechanical presses, Chadwick not only notes the need for bigger bed sizes to handle more complex tools and part features, but also appreciates improved rigidity.

“As the tools get larger and workpiece material gets thinner—appliance customers, for example are specifying 0.020 to 0.025 in. material —clearance in tooling sections can shrink to as little as 0.001 to 0.0005 in. There’s no to run those critically toleranced dies in older presses, unless you want to watch your dies head to the toolroom for maintenance every other run.”

Already Chadwick has seen noteworthy improvements in die life from his new presses. “How else would I be able to justify the investment?” he asks. “For example, one of our dies that stamps an appliance part, when run on one of our older (15 yr. old) presses, required maintenance after every 100,000 hits. Running the tool on our 660-ton Aida allows us to make 250,000 or more hits between maintenance cycles.”

While adding to his press inventory, Chadwick took the opportunity to rearrange the shop floor and improve material flow. Earlier this year he added 75,000 sq. ft. to one side of the building and located all 14 of his automatic presses, including three big-bed transfer presses, into the addition. He looks forward to welcoming four more presses to the new space soon. MFView Glossary of Metalforming Terms

See also: Aida-America Corp.

Technologies: Stamping Presses