Urban Legends, Myths and Half-Truths

March 1, 2011Comments

Wikipedia defines an Urban Legend as “a form of modern folklore consisting of stories usually believed by their tellers to be true.” As with all folklore and myths, the designation suggests nothing about a story’s accuracy, only that it is in circulation, exhibits variation over time and carries some sort of significance that motivates a community to preserve and propagate it.

The tool and die making community has its fair share of folklore. For example, many die-making rules of thumb have been repeated by so many, for so long, that we’ve come to accept them as absolute fact. We no longer recognize them for what they really are: urban legends, myths and half-truths.

Here are five examples:

1) Maximum acceptable burr height for a metal stamping is equal to 10 percent of sheet thickness.

This statement would be true if all stampings were less than 0.050 in. thick. When burr height begins to approach 0.003 in., the burrs begin to become quite noticeable; in some instances, burrs taller than 0.005 in. can even be dangerous, potentially cutting assembly workers. For materials greater than 0.050 in. thick, the 10-percent rule of thumb is unreasonable. My advice: In the absence of a drawing specification, limit burr height to 0.005 in. or less, when practical.

2) The smallest hole diameter in a metal stamping must be equal to or greater than the material thickness being punched.This is simply untrue. Metal stampers routinely pierce hole diameters less than material thickness every day. This task can be accomplished by using quill punches in a supporting body, or by using precision die components in conjunction with guided strippers to support the punch points, and floating punches to ensure accurate alignment.

However, the above statement would be true if it began like this: “To avoid increased die complexity and higher tooling costs, …”

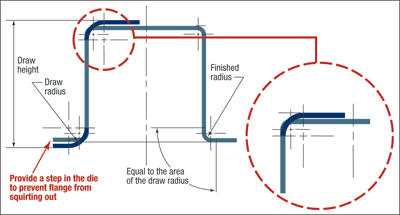

3) Maximum press speed for deep drawing must stay within the recommended draw-speed limits for the material being formed.

The problem with this statement is that it references recommended draw speeds commonly found in die-making handbooks and metal-stamping publications that is sometimes erroneously repeated in seminars.

|

| Courtesy of Arnold Miedema, Green Meadows Engineering |

Need proof? Several die-maker handbooks recommend a forming speed for low-carbon steel between 55 and 80 ft./min., depending on the grade. Yet, a 1999 press release from U.S. Baird Corp. reported steel parts being drawn to more than 2 in. deep running at 285 parts/min., which translates to a slide velocity nearly seven times the recommended limit found in the handbooks.

So what’s the problem? The forming speed in many handbooks and other literature are likely based on E.V. Crane’s book, Plastic Working of Metals and Non-Metallic Materials in Presses. These forming speed limits, first reported in 1931, were based on galling criteria—conditions created by the lubricants, tool steels, sheetmetal alloys and tool-making practices of the time. Since then, new lubricants, steel- and tool-making practices, surface finishes and coatings have changed the conditions for the onset of galling. How many press shops are limiting forming speeds and productivity by using old data? This may be the most-propagated and most-believed urban legend in the industry.

Webinar

Webinar