New Press Controls Push Press Uptime Higher, PPMs Lower

November 1, 2009Comments

An investment in state-of-the-art press- automation controls delivers a boost in uptime and a significant drop in internal PPM, and frees up the toolroom to focus on sensor installations rather than emergency die repairs.

Henry Ford once said that if you need a machine and don’t buy it, then you ultimately will find that you have paid for it, but don’t have it. In the metalforming and fabricating arena, Ford’s perspective easily applies to press controls, where significant technology advances have continued in spite of the economic climate. State-of-the-art controls offer increased ability to handle greater numbers of sensor inputs, and boast a host of new gee-whiz features. Now it’s up to metalformers to learn how to make use of such features to collect and convey press-line data over wireless networks, and to direct and optimize the functions of all of the equipment in a press line, including servo feeds and automated end-of-line packaging systems.

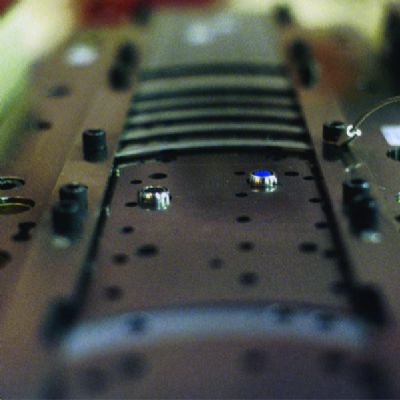

A transfer-press operator takes a look at the tonnage monitor’s plan view on the SmartPac2 to check peak tonnage at each corner of the press for each stroke. The tonnage monitor also provides tonnage history, tracking load throughout the stroke (left) and comparing it to the maximum tonnage curve of the press.

Those that attempt to handle complex projects with large, sophisticated and complex dies while using the control technology of yesteryear soon come to realize how astute Henry Ford’s comment was. Bottom line: Metalformers need to upgrade to newer press controls, or run the risk of “payng for it” by losing vital control over what has become a growing list of process variables. This loss of control can cause unscheduled downtime in the pressroom and wreak havoc on part quality.

Seeing the Handwriting on the Wall

One metalforming company that saw the handwriting on the wall and realized that a press-automation control upgrade not only would easily provide a quick return on investment but also prepare it for future growth and prosperity, is appliance-industry supplier nth/works. The Louisville, KY stamper, which also supplies the automotive, electronics and HVAC markets, undertook an intensive program late in 2007 to upgrade the controls on all 36 of its mechanical presses.

“Tool complexity really took off on us,” says nth/works’ sensor-applications specialist Jason Chanda, “to handle rapidly increasing aesthetic requirements from our customers.” Doug Hogan, director of sales and marketing, adds, “More often, we’ve been quoting jobs with drawn features whose dimensions stretch along several different forms, which are very challenging to check and verify. As we take on more of this type of work, we’re required to take our in-die sensing to a whole new level.”

The firm operates presses from 75- to 1100-ton capacity; bed size reaches 240 in. on a couple of transfer presses and some dies contain nearly 50 sensors. For sure, state-of-the-art press controls would be needed on its presses as nth/works continued to take on these types of complex dies. But the need for additional sensor inputs represents just one cost justification for the level of investment needed to upgrade three dozen presses.

|

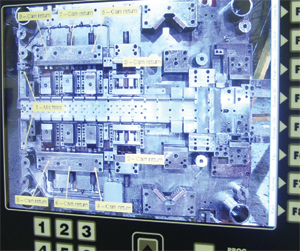

| An Info Center option for the controls allows press operators to download setup sheets, drawings and detailed photos of complex dies. |

“From an executive level, we discussed a handful of items that convinced us, back in 2007, to commit to attaining the highest level of press-automation control technology available,” says Hogan. “Escalating die complexity, with more motion occurring in the dies, more cam forms and pierces, in-die tapping, etc., required us to upgrade our sensing program to ensure that we captured all of those variables.

“We also did a quick study to determine the average cost of a die crash,” continues Hogan, “and to look at cost justifying an upgrade to our press controls from that perspective. Our focus there was not as much on those crashes that cause catastrophic damage, which are few and far between, but rather on the production disruptions that may go unreported and unnoticed by management. These events individually don’t create big losses, but collectively add up to big losses in efficiency that ultimately cost the company plenty.”