ADEA and Title VII EEO cases must wear different legal attire. Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc., 129 S.Ct. 2343, No. 08-441 (6/18/09).

The Modern Day Goblin—Disparate Treatment in the Name of Preventing Disparate Impact

A goblin is a mischievous, annoying little creature that loves to create and prey on conflict. In Ricci v. DeStefano, the U.S. Supreme Court recently addressed what is becoming a more common workplace goblin—discrimination to avoid discrimination.

What does that mean? Title VII prohibits two types of discrimination. One is the disparate treatment of people (intentional acts of employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin). The other is a disparate impact on people (policies or practices not intended to discriminate but that have a disproportionately adverse effect on minorities).

In certain narrow cases, an employer may engage in one form of Title VII discrimination in the name of avoiding the other. But how does the employer know what to do?

In Ricci, the city of New Haven faced this issue. The city was using examinations to identify firefighters best qualified for promotion. The results of the exam showed that white candidates had outperformed minority candidates. This caused quite a dilemma for the city. If it certified the results, it ran the risk of minority employees suing under Title VII, claiming that the examinations were discriminatory. If it threw out the results, it ran the risk of white employees suing under Title VII claiming that throwing out the exams, since such action was based on race, was discriminatory.

To the city, this seemed to be one of those situations where it could engage in discrimination in order to avoid discrimination. For example, the city could certify the exam results, which could result in the disparate treatment of minority employees, but avoiding a disparate impact against white employees. On the other hand, the city could throw out the results, which could result in the disparate treatment of white employees, while avoiding a disparate impact against minority employees. The trick was deciding which one to do.

Picking what the city felt was the lesser of two evils, it threw out the results. As feared, white firefighters sued, alleging that discarding the test results discriminated against them based on their race in violation of Title VII.

Borrowing from equal protection law, the court applied a “strong basis in evidence test.” This means that in order for a government to permissibly engage in disparate treatment in the name of avoiding a disparate impact, there must be a “strong basis in evidence” that the disparate treatment was necessary.

The question before the court was whether avoiding a disparate impact against minority employees was a strong enough basis to justify the disparate treatment of the white employees (that is, throwing out the exam results).

According to the court, the city could demonstrate a strong basis in evidence if it could show that, had it not thrown out the test scores, that it would have been liable under Title VII based on an action from the minority employees. But fear of litigation alone does not rise to the level of a strong basis in evidence. In addition, the court determined that a showing of significant statistical disparity alone (whites outperforming minorities) is far from a strong basis in evidence that the city would have been liable under Title VII had it certified the test results.

|

The court found that the city could have been liable under Title VII for certifying the exam results only if the exams at issue were not job related and consistent with business necessity, or if there existed an equally valid, less discriminatory alternative that served the city’s needs but that the city refused to adopt. The court found no substantial basis in evidence that the exam was deficient in either respect. Therefore, because there was not sufficient evidence that the city would have been subject to a Title VII claim by minority employees if it had not rejected the exam results, the city did not have a strong basis in evidence to reject the results.

The court found that the city could have beenWhat if the city had taken the opposite approach? Would certifying the exam results have been a strong enough basis in evidence to justify the disparate treatment of the minority employees? There really is no to know how the court would have ruled had the city taken the opposite approach. However, now that the court has ruled on this fact pattern, the court noted that if the city were to face a disparate-impact suit from the minority group (based on the certification of the exam results), then in light of the court’s holding, the city can avoid disparate-impact liability in that case based on the strong basis in evidence that, had it not certified the results, it would have been subject to disparate-treatment liability (since it actually was subject to that liability).

Senate Bill 1580— The Ghost of OSHA Future?

The court found that the city could have beenIt’s labeled as the “Protecting America’s Workers Act.” If passed, this bill would forever change how stakeholders would view OSHA.

The court found that the city could have beenWhat is this bill’s proposed provisions? To increase legal protections to job-hazard whistleblowers by prohibiting employer discharge or discipline any worker who refuses to work where the employee “has a reasonable apprehension that performing such duties would result in serious injury impairment of the health of the employee or other employees.”

The court found that the city could have beenWhat is this bill’s proposed provisions? To increase legal protections to job-hazard whistleblowers by prohibiting employer discharge or discipline any worker who refuses to work where the employee “has a reasonable apprehension that performing suchNew time limits are placed on the Department of Labor to process these cases; a new monetary sanctions clause including attorneys fees and investigation prosecution costs is proposed for these types of cases against violating employers; and a new admonition against employers adopting policies that discourage employee reporting work-related injuries or illnesses. Most of these might be considered tightening up with specific protections already in the general OSHA law prohibiting job safety complaint discrimination.

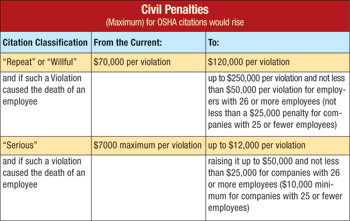

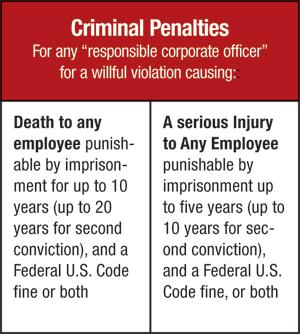

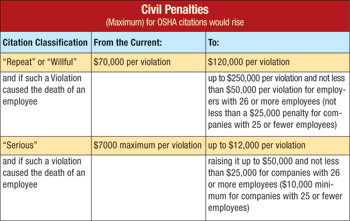

The court found that the city could have beenWhat is this bill’s proposed provisions? To increase legal protections to job-hazard whistleblowers by prohibiting employer discharge or discipline any worker who refuses to work where the employee “has a reasonable apprehension that performing suchThe big proposed OSHA changes statute would come under a section labeled “Title VII—Increasing Penalties for Violators.”

If these drastic penalty proposals become law, employer appeals of OSHA citations could be predicted to exponentially escalate. Any final order citation which could lead to repeat or willful future charges would present a major risk, both corporate and individually. And since intentional workplace tort lawsuits these days frequently include or focus upon any third-party safety audit or maintenance consultants as defendants, who is going to be performing safety audits, safety certifications or maintenance certifications for employers? MF

Technologies: Safety