Servo Press—a Centerpiece of Strategic Expansion

September 1, 2012Comments

Here today, gone tomorrowstampers know too well that jobs on the floor today can be on a competitor's floor tomorrow. That's why managers at Batesville Tool & Die strive to leverage new technology to stamp difficult parts. Its latest fulcrum: an Aida servo-drive press.

Taking on very complex and increasingly large, high-tonnage automotive stamping jobs—that’s how Batesville Tool & Die (BTD) CEO and president Jody Fledderman characterizes his company’s focus over the last several years, as well as its approach to research and development.

“Figuring it out,” as Fledderman says, often means leveraging new technology, well before many other stampers make the same leap of faith. Such is the case with BTD’s most recent investment, an 800-ton Aida servo-drive press. It’s the kingpin of the company’s most recent expansion, its first-ever “strategic expansion,” says Fledderman, to allow for future work. This as opposed to the capacity-driven expansions company managers had become familiar with in the past.

“As a management team, there are certain product lines we want to get into,” shares Gene Lambert, BTD vice president of sales. “Big deep-draw programs are one example. We believed we needed to add capacity for this type of work, and we didn’t want to just add capacity, we also wanted to add technology.”

Technology came not just in the of the servo press, but also via a 1200-ton conventional straightside mechanical press. It’s outfitted with a three-axis servo-transfer system, the firm’s first press-mounted servo system. Previously, it ran all transfer dies using die-mounted servo systems.

“The world is a different place than it used to be,” notes Fledderman. “We’re trying to do a better job of selecting who we want to do business with, rather than als having the customer positioned to select us. Having servo-drive press technology helps us accomplish that strategic goal. We can be more selective about the products we make, and the customers we serve.”

Fast-forward to mid-2011 and it’s no surprise that Fledderman, his brother Jay (vice president of manufacturing) and the rest of the BTD management team saw servo-drive press technology as a ticket to a brighter future.

Removing Restrikes from the Equation

Summarizing its experience with the servo-drive press after running it in production, as well as in tryout to troubleshoot dies running on other presses, BTD’s management team says, in concert: “We’re getting better part quality and consistency, at a faster pace.”

Describing the first production job run on the servo-drive press, Jay Fledderman describes the productivity and quality gain realized from moving a progressive die from a conventional 1200-ton press to the servo-drive press.

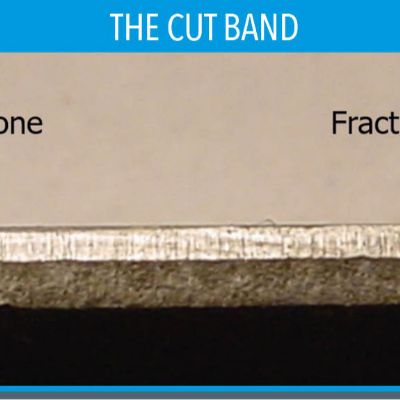

“The die stamps seat side brackets,” Fledderman says, “to the tune of 36,000 parts/week, about 20 percent of press capacity.” Brackets are of 0.156-in.-thick 80-KSI high-strength low-alloy steel. They’re stamped two-out from 15-in.-wide strip over 10 die stations.

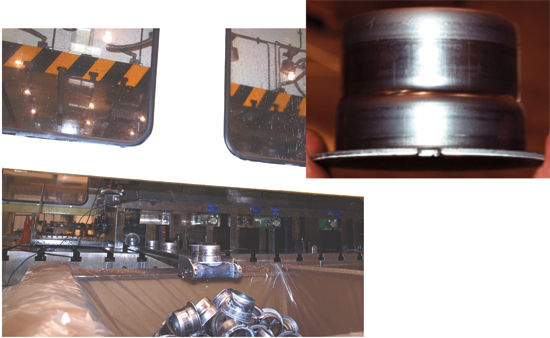

BTD moved this deep-drawing job from a standard mechanical press to its servo-drive press and enjoys more than a 20 percent increase in throughput as a result. The servo press runs the part, of 0.085-in. cold-rolled steel, in the pendulum mode at 52 strokes/min. Critical tolerances are the ID/OD, formed to ±0.006 in. Watch this press run by viewing a 2-min. video in our Multimedia Center.

“We had run the job for years on one of our two 1200-ton presses,” he continues, “learning to live with and compensate for as much as 145 tons of reverse tonnage. While the addition of hydraulic dampers on the press brought snapthrough force down to 115 tons, our press operators and diesetters found the dampers burdensome and cumbersome.”

Moving the part to the servo-drive press and redesigning the process to reduce ram speed at certain portions of the stroke, during piercing and coining, brought snapthrough down to a manageable 55 reverse tons.

“We’ve found the press to be extremely adjustable in terms of how many times within each stroke we can specify ram speed,” says Robert Holtel, vice president of tooling. “This capability not only helps with snapthrough, but it also improves flatness on coined sections of the bracket, and has reduced the amount of adjustments we need to make within the tool for the form shape. Before, the hit at the bottom of the stroke was so brief that we had to overform to control part dimensions on springback. This proved very inconsistent. To get servo-press-like performance on the 1200-ton mechanical press, we would have had to add a couple of restrike stations to the die.

“With the servo-drive press, we nearly stop at bottom,” Holtel continues, “while overall cycle time has decreased by more than 15 percent, with the press running at 40 strokes/min. Scrap rate is down, and we have fewer, if any, broken punches.”