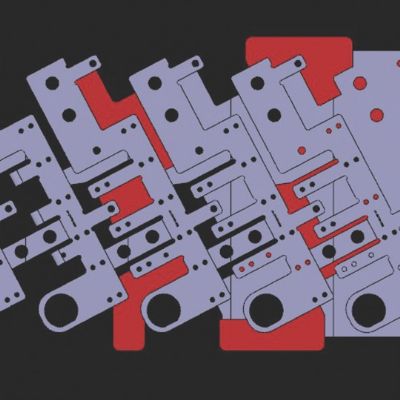

Can You Provide Guidelines for Designing Progressive Stamping Dies?

January 25, 2025Comments

Most of my readers are familiar with my “10 Tooling Laws;” here I present my “10 Design Laws.”

1. Have no goal except perfection.

Start with a clear objective. Balance the overall tool cost with stability, quality and hits per service requirements. Think beyond the task of just designing a die. Look for the pitfalls that can crop up during die maintenance and press setup. Design in and poka-yoke (mistake-proof) the die for repeatability. For example, design all cutting and forming inserts so that they cannot be installed upside down or backward.

2. Minimize strip lift and die stroke.

Vibration is the poison to all tooling. Stagger the cutting punches and minimize strip lift (the height of the lifters). This allows you to minimize the die stroke and thus impart better dimensional stability into your stampings, due to less tooling movement. A reduced die stroke yields reduced ram speed. Less movement results in less shock and vibration. Remember, carbide is like concrete and will disintegrate before it wears.

3. Design stock lifters as needed to keep the strip level.

The strip must remain parallel during the entire press cycle—especially as the die closes. Ensure that the space between lifters is such that it will not allow the strip to sag. If, by design, you are doing work as the stripper-plate springs begin to compress, the lifters must be strong enough to clamp the strip against the face of the stripper plate to maintain a consistent part. When forming with spring-loaded punches, calculate the force required to complete the form and double the spring load behind the forming punch to ensure that it does not back up during forming.

4. Balance the die in the press.

The goal, by design, is for the tool to tend to close evenly on the four-corner die stops naturally. Remember, every tool and press has some lateral play, which, in turn, affects stability and tooling life. The guide pins and bushings must be robust enough to overcome these lateral forces. If, for example, heavy forming occurs on the right side of the tool, consider adding balancing springs on its left side.

5. Design for repeatability.

As a tooling designer, you must design the maintenance process into the plan. This often is overlooked. If a punch can be shimmed to the point that it interferes with the stripper or other tooling, include shimming instructions (including a maximum) on the print. All purchased components, such as springs, screws, dowels, keepers and shims, must be designed and specified. The die builder and toolroom maintenance team should never have to guess your design intentions.

6. Design out people skills, and design in machine capabilities.

Machines make components and people maintain them. Skill levels vary. Do not design components that require a highly skilled toolmaker to ensure repeatability. Wire electrical discharge machining can deliver the accuracy and surface finish required. Clearly spell out polishing and surface-finish requirements on the print, including all corner breaks where required.

7. Design for zero development time.

Success is based on understanding what to expect from each station in your progressive die. If something needs redesigning during development and grooming of the tool, then you did not achieve the original intent the first time. Design to meet capability requirements. In the design phase, get input from the tooling and setup people who run the tools. This is one of the single largest factors that will impact your success. Look at similar existing stamping dies and their output relative to the design and product dimensional stability. Design in risk mitigation. For instance, for trims that may need to change, the design should incorporate ways to make changes on the fly easily. Add extra pilots where you are concerned that the strip may pull during heavy forming or coining. Add idle stations where they may be needed.