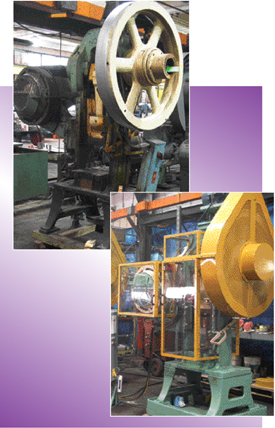

Mechanical Presses: Rebuild or Buy

December 1, 2007Comments

When is it best to rebuild the press you have and when does it make sense to buy a new press instead? A press-rebuild specialist weighs in.

Presses wear. Ideally, it’s the press parts designed to wear, such as bushings, liners, packings and seals, that prevent stresses on major components. As these wear parts do their job, they require attention and replacement. Sometimes they get that attention and sometimes they don’t. Whether preventive maintenance catches and resolves these wear issues or not, eventually the constant pounding takes a toll on the press. At some point, management must decide if press problems can be solved via a rebuild or whether buying a new press is the sound option.

What You’ll Get with a Rebuild

Typical mechanical-press rebuild time averages about six months, according to Peter Campbell, president of Campbell Press Repair, Lansing, MI. A rebuild typically runs 40 to 60 percent of the cost for a comparable new press.

Right off the bat, rebuilding entails removing excess clearances in bushings and wear surfaces, and replacing these parts to return them to original specs. These parts include main and connection bushings, ram wear plates, clutch, brake and air counter balance perishables. Sometimes during a rebuild you may find broken and damaged components such as crankshafts, connections and rams. These parts can typically be repaired and returned to service all in an effort to return the machine to working tolerance.

Also, the press may be disassembled down to its bare components—each inspected and replaced if necessary, along with replacement of all bushings, bearings, seals and gaskets. At another level, Campbell notes, press modernization may be in order.

“That may involve a new press-lubrication system, pneumatic system and controls,” he says. “Modernizing also includes addition of safety equipment such as light curtains and die-protection devices, tonnage monitoring and maybe even isolators to provide for leveling and vibration dampening.”