Oil and Photoelectric Sensors

July 1, 2012Comments

State-of-the-art photoelectric sensors are as varied as ever regarding their usefulness in oily environments. Some suppliers advertise their photoelectric sensors as being capable of working within oily environments, while in other cases the sensors seem to be able to ignore oils but are not identified as such in their respective specification sheets.

Regardless of what the specs allow, a stamper should avoid bathing its sensors in oil. Many oils used in stamping dies are filled with microscopic (and sometimes not so microscopic) metal particles. As the oil drips, circulates and washes over any exposed sensors, those miniature metallic particulates abrade the sensor packaging. For inductive proximity sensors, this type of wear is minimal. But for photoelectric sensors, it can be fatal. Even though the packaging of a photoelectric sensor may be rated to withstand oils, the lenses—especially those made of a conventional clear plastic material—can become scratched and eventually dulled into uselessness.

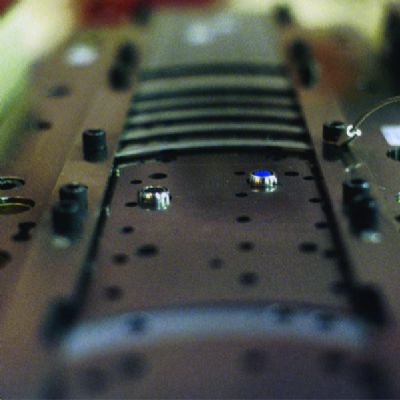

I am a big fan of embedding photoelectric sensors deep within small blocks of aluminum or steel to minimize their exposure to the abrasiveness of oils. A tiny hole in one side of the block allows light to leave or enter the sensor. This hole—carefully developed on a test bench during sensor testing under actual die-mounting condition—is as small as possible without impacting sensor performance. Any abrading oil particles, therefore, would have a difficult time entering the block and washing over the sensor’s lenses.

To further prevent oil from entering the block, a stamper can attach a small airline to the block. Under relatively low pressure, the air being delivered creates positive air pressure within the block, with the air exiting from the small light-beam hole. This positive pressure further prevents the inside of the block from hosting the oil. Caution: Be sure to use clean, pressurized air free from water and oil.

Remember that our primary concern is the preservation of the lens integrity on the sensor. To illustrate this, in my classes I refer to our oils as “subtle liquid sandpaper.”

Why bother with all of this? Well, for one thing, a properly selected photoelectric sensor embedded within an aluminum or steel block should last for the life of the die, if not beyond. If, in our example, such a sensor would be used for part-out detection, imagine how many times the sensor might protect the die from a double hit. No doubt that the extra time and cost to properly protect the sensor will easily be recouped when considering the costs required for die maintenance and repair in response to a double hit.

While the above discussion deals primarily with the physical protection of photoelectric sensors within dies, it is equally important to select sensors that ignore the oils within the die and detect only the target of interest. Their beams primarily are infrared and invisible, as they tend to see (or burn through) oils better than conventional, visible light beams. Back on the test bench, these infrared beams should be tested with the actual oils being used within the die, by spraying the beams of light and checking to ensure that the oil spray does not trigger the sensor.

Modern photoelectric sensors represent spectacular improvements over their counterparts of just a few years ago. Nevertheless, it cannot be overstated: Protect these sensors by carefully bunkering them deep within protective enclosures. Our die environments are exceptionally hostile and unforgiving when it comes to photoelectric sensors. MFTechnologies: Sensing/Electronics/IOT

Comments

Must be logged in to post a comment. Sign in or Create an Account

There are no comments posted. Sensing/Electronics/IOT

Sensing/Electronics/IOTEliminating Pressroom Waste—One Walk at a Time

Manuel Resendes June 10, 2025

Industry 4.0 Applications in the Sheet Metal Forming Industr...

Eren Billur March 27, 2025