Opportunities Outweigh Apprehension When Forming New Metal Alloys

November 3, 2021Comments

There is something reassuring about staying inside our comfort zone, especially as it relates to the stamping of metal-alloy parts. The engineering, manufacturing, quality, and purchasing teams can copy and paste from prior parts, with reasonably high confidence that whatever worked then will work again. However, are these parts the ones your company should pursue?

Review each of your parts with a critical eye as to the value they bring to you and your customer. Customers love low-cost stampings, but these jobs likely will cause metal formers to compete on price. Maybe these parts will reduce your fixed-cost plant burden, but running them also prevents you from using your line time and resources in a manner more beneficial to your bottom line.

One way to seek-out manufacture of value-added stampings is to target those parts formed from advanced metal alloys, such as high-strength steels or aluminum and stainless-steel grades. Doing so effectively requires understanding how stamping these grades differs compared to your current approach.

One way to seek-out manufacture of value-added stampings is to target those parts formed from advanced metal alloys, such as high-strength steels or aluminum and stainless-steel grades. Doing so effectively requires understanding how stamping these grades differs compared to your current approach.

For example, it may be tempting to take a one-size-fits-all approach to tooling and tool construction, but doing so will result in a sub-optimal solution. A D2 tool steel, for example, works well for many plain-carbon-steel parts. However, this alloy contains about 12 percent chromium, as do many stainless steels—and that is the root of the problem. As the sheet metal flows over the tool during stamping, the chromium in the stainless sheet and the tool may weld together, leading to adhesive metal transfer. Addressing this requires using applying a surface coating to the tool or selecting a different tool steel.

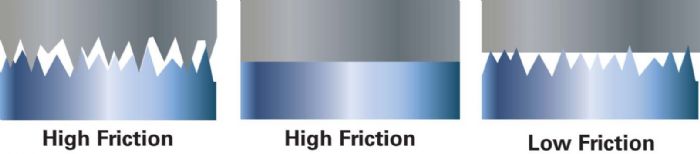

Tool surface-finish procedures also should change based on the chosen sheet-metal alloy. If the sheet and the tool have a high roughness, then the peak tips may break off as the sheet flows across the tool, leading to a high friction condition. High friction also exists with a low-roughness sheet and tool-steel combination, since the forming pressure squeezes out the lubricant between the surfaces. The ideal friction condition is when one surface has a relatively higher roughness compared with the other surface (see the accompanying illustration). However, the typical roughness of sheet aluminum and stainless-steel alloys is lower than that of plain-carbon steels. Aluminum also is softer than steel, so the roughness peaks may smear during forming. This results in particle buildup and an associated reduction in sheet metal flow. The chosen sheet alloy should influence the tool surface finish to minimize this effect.