Know Your Sheetmetal—Aluminum-Alloy Terminology

April 1, 2018Comments

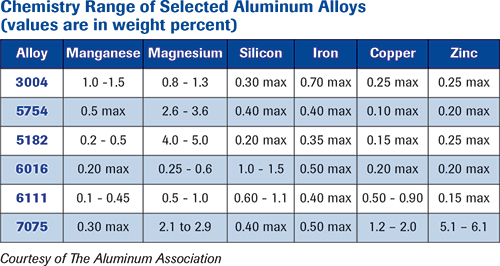

Aluminum alloys are categorized by a four-digit code. The first digit indicates the main element or elements alloyed with aluminum to produce the specific grade. Products with the same first digit are said to be in the same series or family, described by a number followed by three zeroes or “X”s, such as 5000-series or 6XXX-series aluminum. Within the same series, products share basic characteristics and applications.

Beverage-can bodies represent the highest-volume application for 3XXX aluminum alloys, which use manganese as the primary alloying element. Manufacturers produce 200 billion soda and beer cans each year–more than 6000 every second. In sheet form, alloys used to produce the cans are not inherently high-strength, but the draw-and-wall-iron process used in canmaking increases strength while reducing thickness to about 0.1 mm. (Fun fact: Carbonation increases the internal pressure of beverage cans—when stacked in a store display, they do not collapse. It’s even claimed that four six-packs can support a 2-ton vehicle.)

Magnesium is the main alloying element in 5XXX-series aluminum. Alloys in this series offer good combinations of strength and formability. However, higher strength levels introduce an increasing corrosion risk, especially as temperature increases. Alloys in the 5XXX-series may form Lüders lines during deformation, which eliminates their use in exposed applications. (Another fun fact: One-third of global magnesium production is used for alloying with aluminum.)

6XXX-series aluminum uses a magnesium-silicon combination as the primary alloying elements. Like the 5XXX-series, good combinations of strength and formability exist, but here an exposed quality surface can be produced without risk of Lüders or other bands affecting the appearance.

The 7XXX-series grades feature some of the highest-strength aluminum-sheet alloys, but typically do not offer good formability at room temperature. Successful stamping may require forming at temperatures at or greater than 200 C. These products usually are riveted rather than welded, owing to the risk of weld cracking from a large solidification-temperature range. In addition to having zinc as the main alloying element, some grades also contain a combination of magnesium and copper.