“We have seen wider adoption of servo-press technology, and now see metal formers, for example, coming up with creative ways to build their dies to best utilize this technology,” says Lee Ellard, national sales manager for Stamtec.

With basic servo technology established and a high level of servo-press adoption at some progressive manufacturers, metal formers, as Ellard sees it, now are trying to optimize tooling and other line components, materials and processes to best take advantage of what servo presses can do.

On the supplier side, Ellard sees press manufacturers, with basic drive technology in place, changing some control and other components to those from other suppliers.

When seeking to better understand how to leverage servo-press advantages, “metal formers interested in a press where they can run different stroke lengths, i.e., using pendulum motion, they want to know how fast that can run that pendulum,” Ellard says, commenting on current knowledge searches. “That’s the goal, right? Shorten the stroke and speed up the press. At the same time, they are trying to figure out how slow they need to go to properly form the part.”

Tryout, Tryout, Tryout

Of course, with proper programming, servo presses allow for slowdowns during the working portion of the stroke, and rapidity everywhere else, thus optimizing part quality and productivity. Finding those exact speed and force sweet spots will vary depending on the application, the material and the tooling.

“Here, the best advice I can give is to experiment in a press,” Ellard says.

For its part, Stamtec offers die tryout in a number of servomechanical presses under power in its Manchester, TN, location.

“A metal former can come in to test its die and material, and we’ll set it up in the press and let them play,” Ellard says, noting that die makers local to Stamtec also can come in to provide expert opinions on tooling and provide some advice. “It is almost trial and error, but metal formers really need to test servo presses to see what they can do for a particular application.”

“A metal former can come in to test its die and material, and we’ll set it up in the press and let them play,” Ellard says, noting that die makers local to Stamtec also can come in to provide expert opinions on tooling and provide some advice. “It is almost trial and error, but metal formers really need to test servo presses to see what they can do for a particular application.”

Metal formers also should consider forming simulation software, Ellard points out, “as it gives good insight into what can be done in a die with a servo press. Again, testing out an application is so important—things happen that no one really understands or anticipates, such as the actual loss of tonnage and working energy depending on exactly how a metal former is using the servo press.

“It’s really all about forming and working energy, and slide speed,” he continues. “Slide velocity affects how the material is forming, and then a certain amount of working energy is required to do that work. All of this is application-specific.”

A successful tryout described by Ellard involves a metal former looking to form a titanium part that could not be formed cold nor without slow forming speed and dwell time.

“Our press has a mode where the ram comes down and closes the die just enough to where it’s not forming the part, but allowing the die to heat up,” Ellard explains. “The ram dwells for a few seconds during heating, then descends very slowly through the bottom and dwells for just a second at bottom for forming. During tryout we were able to tweak what we call the mold-heating stroke profile, to where the ram dwells the correct length of time in the mold during preheating, then descends slowly to bottom for another dwell, then quickly backs out. This part could not be made using a traditional press or die.”

Flexible Feeds Fuel Possibilities

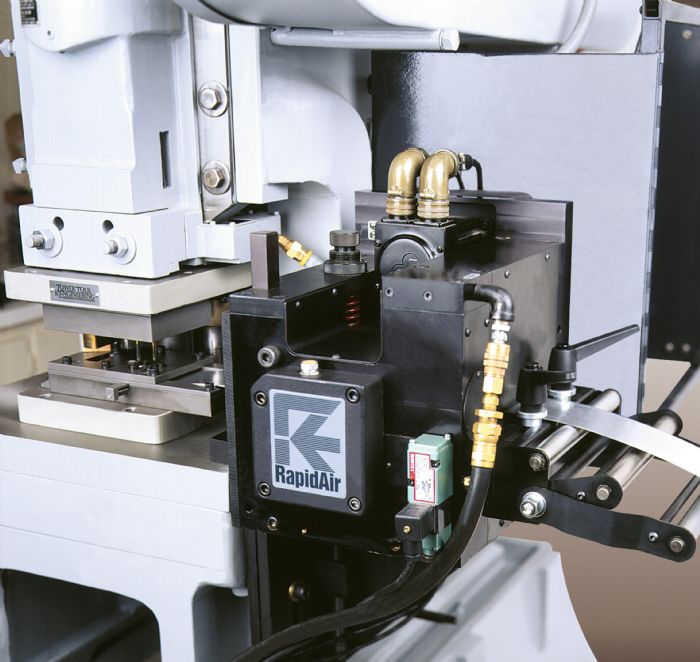

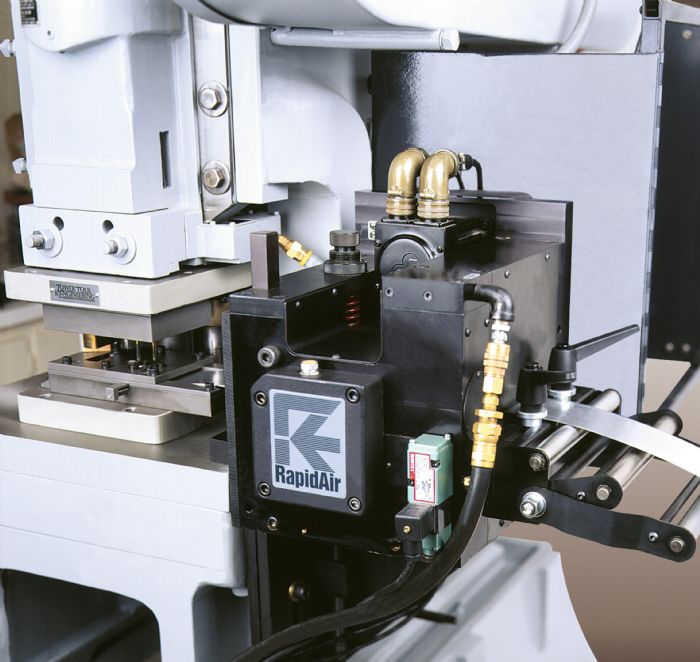

Like Ellard, Brad Nordlof, chief operating officer for feed-system provider Rapid-Air, sees servo technology as enabling the fine-tuning of specific applications. Air feeds represent the majority of Rapid-Air sales, according to Nordlof, but servo-drive feeds are not far behind, with vast job-storage capability, processing power and simplified setup providing some key advantages.

One major benefit: a high production rate. Taking basic information such as strokes/min., and feed length and angle, a servo feed calculates optimum speed as well as acceleration and deceleration. Users can store these job settings or override the settings in specific applications and save those, too. As a result, servo feeds prove ideal for short runs or frequent job changes.

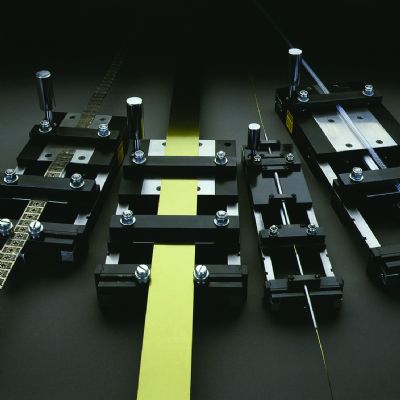

And, servo-feed features that offer similar speed capabilities as found in servo-driven presses may result in simpler, less expensive dies that may be fed diagonally, side to side or in any pattern. Metal formers, with such capabilities in their arsenals, are free to tailor them to applications.

“For special requirements on a servo-press application, we as the feed supplier may have to modify a gag program, add memory or embed a specialized program to enable special back-and-forth movement,” Nordlof says. “But, the specific applications will drive a feed’s use and setup on the plant floor.”

The need to adapt to so many unique applications enabled by servo-press capabilities makes the flexibility of servo-driven feeds so advantageous.

“Once the feed leaves us,” explains Nordlof, “we receive samples on a daily basis… ‘Will your servo feed run this?’ ‘Will the servo drive in your straightener pull this material into it?’ It is up to the metal former to eliminate any catches or obstructions in the tooling, because we can’t control that. We can only say that our equipment will deliver that material into your press for your application.”

In short, while servo-driven press and feed technology certainly is up to the challenge, the array of servo-press applications demands that metal formers coordinate their applications, tooling and equipment to ensure that everything is in tune. MF

See also: Rapid Air Corporation, Stamtec, Inc.

Technologies: Coil and Sheet Handling, Stamping Presses

While servo-drive technology has begun to mature, advancements continue in Industry 4.0 technology that leverages servo presses and other press-line systems in new ways (see On the Precipice of the Smart Pressroom feature article in the MetalForming February 2021 issue).

While servo-drive technology has begun to mature, advancements continue in Industry 4.0 technology that leverages servo presses and other press-line systems in new ways (see On the Precipice of the Smart Pressroom feature article in the MetalForming February 2021 issue).

“A metal former can come in to test its die and material, and we’ll set it up in the press and let them play,” Ellard says, noting that die makers local to Stamtec also can come in to provide expert opinions on tooling and provide some advice. “It is almost trial and error, but metal formers really need to test servo presses to see what they can do for a particular application.”

“A metal former can come in to test its die and material, and we’ll set it up in the press and let them play,” Ellard says, noting that die makers local to Stamtec also can come in to provide expert opinions on tooling and provide some advice. “It is almost trial and error, but metal formers really need to test servo presses to see what they can do for a particular application.”