Deep-Draw Automation Returns Remarkable Results

January 1, 2009 Robotic blank handling--from stack through lubrication and on to a hydraulic press--improves line speed by 25 percent. A double end-of-arm tool simultaneously removes a scrap ring and loads a new blank, with safety ensured as hands no longer enter the press.

|

|

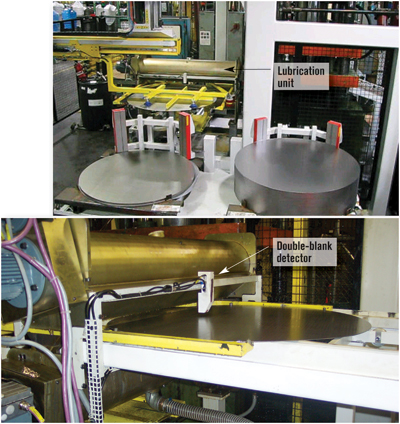

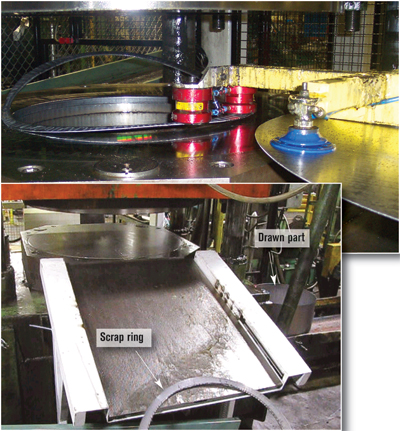

The three-axis press robot (top) stationed at the 300-ton deep-draw press cell takes a 39.5-in.-dia. blank from the palletized stack and prepares to drop it into a centering station. The blank then moves, via a single-axis programmable shuttle (bottom), through a noncontact lubrication system and then is picked up again by the robot for loading into the press. Note the double-blank detector at the entry end of the lubrication unit.

|

No article interview could begin better than hearing the subject say, “This is the most successful capital-equipment project I have ever been involved with.” And that is precisely what Todd Weston, manufacturing engineering manager at Amtrol Inc., exclaimed as we discussed the firm’s recent deep-draw automation project. Amtrol, West Warwick, RI, builds pressure tanks and other commercial vessels for well-water storage, hydronic heating and other applications. A series of production lines—from deep draw to welding and assembly—turn out vessels from 6-in. to 6-ft. dia.

At the head of each tank line sits deep-drawing equipment for forming tank domes. Lines manufacturing smaller tanks—less than 15-in. dia.—host two hydraulic deep-draw presses, while lines for larger products employ one press to make a common dome for tank top and bottom. In all, the 200,000-sq.-ft. plant houses eight hydraulic presses, from 150- to 500-ton capacity. Conveyors automate flow from the presses through secondary processes—fabrication, welding, etc.—and on to final assembly and packaging.

Safety First—But Cost Savings are Nice, Too

A little more than 10 years ago, Amtrol began automating its hydraulic-press operations, all except for the line outfitted with a 400-ton press drawing 22-in.-dia. products. “We can’t justify automation on that particular line,” says Weston, “because volumes are too low, only 160 per day.”

The last press automated by the firm, and the project that Weston spoke to me about, also manufactures 22-in.-dia. product, “but with a slightly less draw depth than the lower-volume manually fed operation,” Weston says. The 300-ton hydraulic press draws 1200 domes a day. When Amtrol initiated the automation process for the press, in mid-2007, the stated goal of the project, says Weston, was safety-related. “To get the operator’s hands out of the die,” he explains. Also of concern was repetitive-motion stress, as operators had to load and unload blanks—39.5-in. dia. and of 0.062-in.-thick draw-quality Type 1008 steel—that weigh 35 lb. each.

“In addition to the operator having to load the blanks into the press,” says Weston, “he first had to move each blank from the stack and into and out of a lubrication station. And, after every hit in the die, the operator had to remove a scrap ring that remains on top of the die from the previous stroke.”

|

|

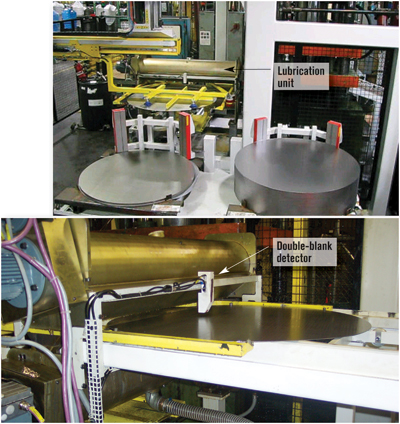

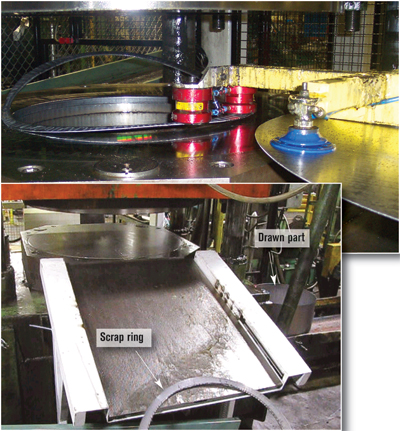

The press robot’s end-of-arm tooling (top) features a pair of end effectors—suction cups to manipulate the blank and magnets to remove the scrap ring from the previous press stroke. As the robot deposits the scrap ring onto a conveyor it drops the blank onto the die. Finished, drawn parts can be seen (bottom) exiting the press on a conveyor.

|

During production, as the punch descends it pinch-trims between the cutter and the die ring. The drawn dome leaves the press trimmed and the scrap ring remains on top of the die. Amtrol then performs a beading operation on the edge of the dome, and also uses the trimmed edge to track the weld joint during assembly.

Automation Opens Bottleneck

Before Amtrol completed the press-automation project, the 300-ton press ran at 3 strokes/min., which restricted production-line capacity on the popular 22-in. product used to manufacture the company’s line of well tanks. One of its long-term goals, says Weston, is to evolve into more of a just-in-time delivery cycle and to cut its number of inventory turns in half. It maintains a warehouse facility near the factory, and hopes to reduce its reliance on warehouse storage and move more toward direct shipping from the factory.

“Direct shipping accounts for 10 percent of our business now,” Weston says, “and we hope to get to 50 percent. Eliminating the bottleneck at the press, through this recent automation project, represents a big step in that direction. We’ve been able to increase the production rate to 4 strokes/min., a 25 percent gain.”

Blanks Handled from Stack to Rack

To automatically handle blanks from stack to rack, Weston and his team at Amtrol invested in an automation system designed and built by AP&T North America, Inc., Monroe, NC. Included is an AP&T SpeedFeeder 60 three-axis press robot; two floor-mounted blank-storage magazines, each with a maximum stack height of 15.75 in. and four fixed permanent magnets used to separate the blanks; and a single-axis programmable blank feeder with double-blank detector, which shuttles blanks into a new noncontact lubrication unit.

The SpeedFeeder 60 lifts blanks from the stack and deposits them onto the blank feeder for loading into the lubrication unit. The SpeedFeeder then picks up the lubricated blanks at the opposite end of the lubrication unit and loads them into the die. It carries a unique double end-of-arm tool designed to simultaneously carry the scrap ring off of the die and deposit it onto a scrap conveyor while at the same time depositing the lubricated blank onto the die. Magnetic lifters handle the scrap ring as suction cups grip the blank. Finished, drawn domes drop below the press bed onto conveyors for transport to downstream operations.

“Ensuring that we have removed the scrap ring from atop the die was a critical requirement in automating the process,” shares Weston. The firm at first tried a single sensor to indicate to the press control when the scrap ring had safely exited the die. However, it quickly found a more reliable solution when it installed a full light curtain at the entry end of the scrap conveyor so that, regardless of where and how the end-of-arm robotic tool deposits the ring onto the conveyor, the light curtain senses its presence and then signals the press control to allow the press to stroke.

“Reliable communication between the AP&T line and the press control was a critical success factor for the project,” adds Weston. “An Allen-Bradley unit at the press communicates with a Siemens control on the automation equipment. AP&T integrated the controls to ensure, job one, that the feeder does not enter the press bed until the automation control receives the appropriate signal from the press control and, job two, that the press does not cycle until the scrap ring has been removed and deposited onto the scrap conveyor.”