Stamping Controls Evolve to Meet Current, Coming Challenges

March 1, 2015 Trends in data reporting, cellular manufacturing and good-part verification drive advances.

Like other technologies that couldn’t keep up with the times, controls that only flashed a light to warn an operator of a stopped stamping press have long outlived their usefulness.

Like other technologies that couldn’t keep up with the times, controls that only flashed a light to warn an operator of a stopped stamping press have long outlived their usefulness.

As manufacturers have expanded their expectations for press controls, the technology has evolved, and will continue to evolve.

“In the 1970s and into the ’80s, metalformers wanted a control that would make the press go down and up,” explains Dean Phillips, sales engineer for Link Systems, Nashville, TN. “They then sought more—slide adjust, counterbalance and other functions to reduce the amount of time that operators required to perform such tasks.”

Today, offers Phillips, one-button operation is the ideal.

“The operator selects a job and the press controls take over,” he says, “telling all of the workcell components what to do.”

And there’s more…much more.

Communication Across the Workcell

Suppose a metalformer wants to reduce changeover time to 5 min. Of course that means investing in die-change components for the task. But, says Phillips, it also means ensuring that the controls can make it happen.

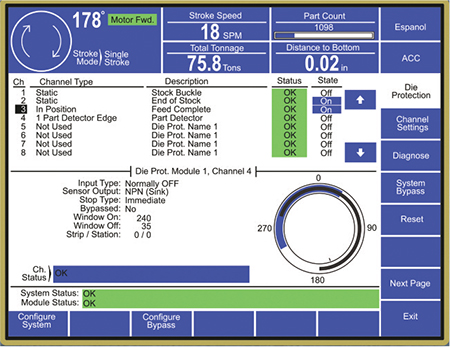

“Controls must talk to each other for projects such as this to succeed,” he explains. “Today, controls can communicate with robots, transfers and other cell components. In the past, press controls did not address components or particular processes if they were not in and of the press. Controls now have expanded their reach, especially given welding, assembly, clinching and other actions performed within the tooling to produce a more complete part. They can even alter tooling to improve tolerance on the fly.”

|

| Unlike in years past, with today’s press controls, an operator needs only to enter a job number and all press functions are updated—shut height, counterbalance, press speed, die protection, feed length, lubrication sprayers, etc.—and adjusted to their proper settings. Look for continued evolution—it’s happening even now—with the press control overseeing setting and monitoring performance across an entire workcell. |

As thinking evolves from stamping as an assembly-line process to cellular manufacturing, controls will enable the evolution.

“The integration of ancillary devices into a single-button operation so that all systems are communicating—that’s where controls are heading,” Phillips says. “Enter a job number and all press functions are updated—shut height, counterbalance, press speed, die protection, feed length, lubrication sprayers —all adjust to their proper settings. The same occurs with transfer systems, robots and other cell operations such as assembly and material handling.” Metalformers want a more complete part coming off of the press, driving controls to adapt to the increased use of cellular manufacturing, and to communicate more closely with the entire cell.

Gathering and Sharing More Information than Ever

Metalformers and their customers increasingly crave information, for a variety of reasons, and controls have developed capabilities to gather and share it.

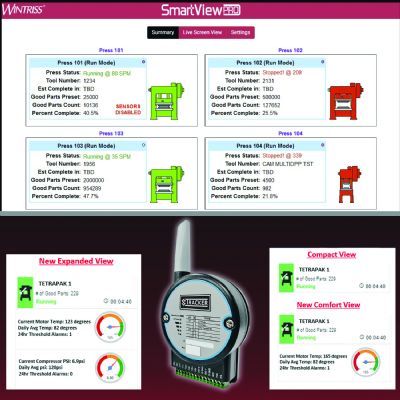

|

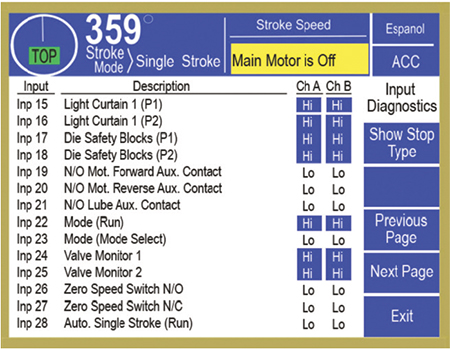

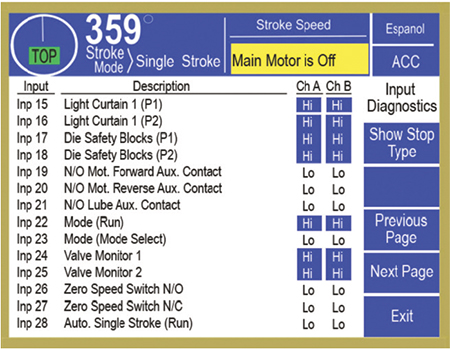

| Press controls increasingly offer diagnostic capabilities, eliminating downtime related to a technician having to inspect the press line in detail. |

|

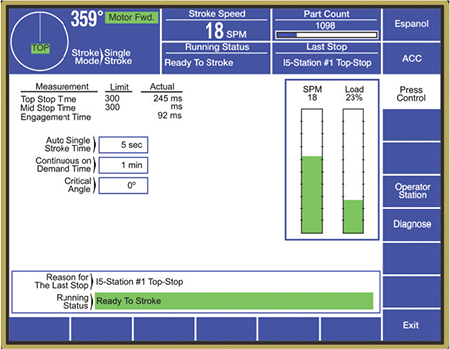

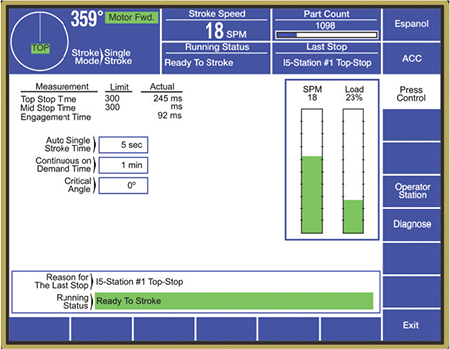

| Simple, yet detailed control displays provide critical press-line information to the operator, and feed into company-wide systems that assist in scheduling and performance assessment. |

|

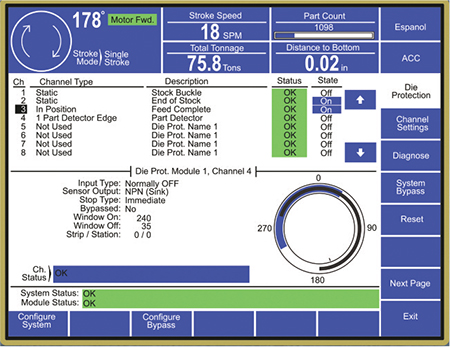

| Die protection is a critical function routinely handled by today’s press controls. |

“Controls can provide real-time information on job status and when a job will complete, allowing metalformers to have fork trucks rolling to position the next die or change part bins,” Phillips says. “Controls also integrate with MRP and ERP systems (providing offline updates) to improve, for instance, the tracking and ordering of materials. To inform software systems and networks, and aid company decisionmakers, press controls gather and relay information to monitor tool wear and equipment performance, and plan maintenance.

“Manufacturers,” he continues, “need specific information on, perhaps, why a press has stopped. They can’t afford the downtime for a technician to come over and spend an hour or more investigating to find that an operator didn’t plug the die block in or turn the air pressure back up. Controls identify these issues and report them in plain English or other languages. This capability helps operators quickly diagnose and correct simple errors.”

In more complicated situations, according to Phillips, technicians require diagnostic tools in the control that show input and output status, with less daisy-chaining, an architecture that increases troubleshooting time. In addition, due to arc-flash regulations and electrical-shock hazards, technicians can examine inputs and outputs shown on the control screen instead of entering a hot electrical panel.

Beyond that, controls today provide an abundance of historical data used to create baselines and chart performance for a variety of uses.

“Controls gather information such as tonnage curves of a tool, so that a company can compare curves over time,” Phillips says. “A manager can compare graphs and determine that a tool does not run like it had prior, and investigate why.”

The trend points toward manufacturers seeking data gathering and automatic reporting to the point that some actuating mechanism on the press or in the cell will do something with that information, according to Phillips. Also, because control systems no longer are expected to just monitor and report on the press but on ancillary systems as well, more diagnostic trouble codes are needed, and efforts are underway to add sensoring and provide more codes.

Video

Video