Why Work Hardening Is So Important

September 1, 2009Comments

An attendee loudly made an important comment during a recent PMA seminar on sheetmetal forming. “When my steel work hardens during forming, it stalls the press. Where can I purchase steel without work hardening?” The ensuing discussion explained how stretchability and bendability are possible only when materials work harden. The real solution would depend on the actual cause of the press stalling—insufficient tonnage or lack of energy replacement. Inserting steel without work hardening would only create a major disaster.

|

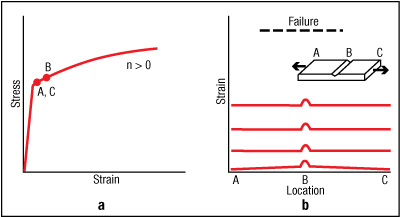

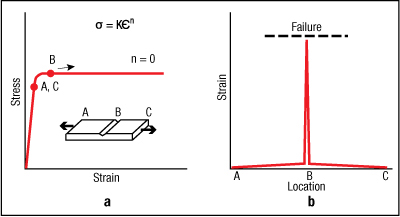

| Fig. 1—Schematic a shows how zone B continues to deform to failure at a constant stress, while zones A and C remain elastic. Schematic b shows the resulting severe strain gradient. |

Assume a sample of steel without any work hardening capacity is being stretched (sketch inserted into Fig. 1a). The sample has a constant cross-section from end A to end C except at zone B. Here a scratch, slight reduction in thickness, or some other reason creates a reduced cross-section at zone B. Since stress is pulling force divided by cross-sectional area, the stress level at B is higher than the rest of the sample. To initiate deformation, the pulling force is slowly increased and then halted when zone B reaches the yield strength. Since the remainder of the sample (zones A and C) has less applied stress, these locations are still in the elastic region (see data points on the stress-strain curve in Fig. 1a.) However, once started zone B continues to elongate and reduce its cross-section, thereby moving to the right along the flat stress-strain curve. This deformation continues until the sample breaks at zone B.

Since the rest of the sample is still in the elastic region, the stress goes back to zero and any elastic deformation is reversed as the sample breaks. This results in a very severe and highly localized strain gradient (Fig. 1b). The average useful stretch over the entire length of the sample is almost zero, making steel without work hardening useless for almost all practical stampings containing a tensile force. This includes the outer fibers of a bending operation that also are subjected to stretching.

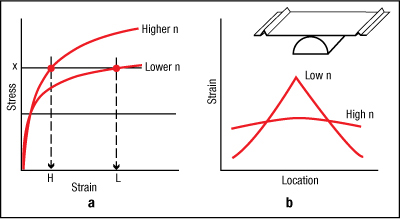

| Fig. 2—Schematic a shows work hardening forces zones A and C to follow zone B up the stress-strain curve as the tensile force is increased. The strain distributions in schematic b remain almost flat at different amounts of deformation. |