Processing Aluminum Stampings

June 1, 2014Comments

Aluminum alloys can successfully be formed into complex shapes—automotive body panels for example—using existing pressroom production equipment. Production examples include inner and outer door panels, hoods, deck lids, lift gates, cross members, and structural and reinforcement components. Aluminum properties differ greatly than those for steel, which means that aluminum deforms differently during stamping. This requires a die- and process-design strategy that accounts for these differences.

|

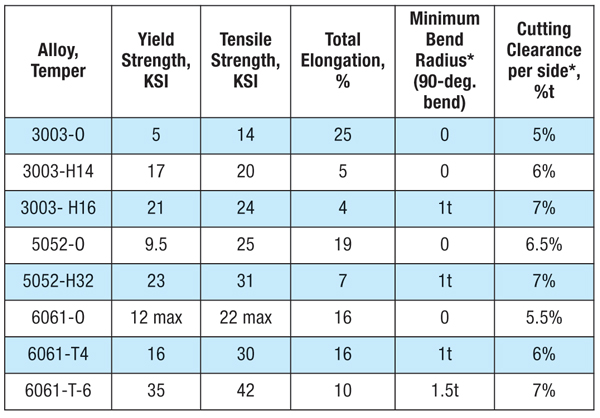

| Table 1—From ASM Specialty Handbook: Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys |

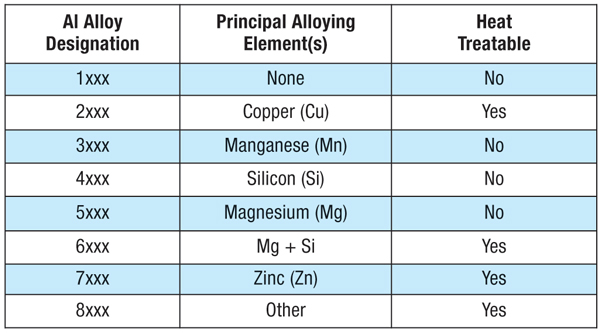

The first step: Understand the alloy and temper designations for the specific stamping being processed. Aluminum alloys are designated by a four-digit code that describes their primary alloying elements (Table 1).

The 1xxx series alloys essentially are commercially pure aluminum—very soft and formable—and are not used where strength is a prime consideration. They typically find use in electrical and chemical industries.

The 2xxx series alloys exhibit high strength, toughness and, in some cases, weldability. They do not resist atmospheric corrosion as well as other aluminum alloys do, so they typically are painted or clad for added protection.

The 3xxx series alloys are the most widely used—stronger than 1100 but still readily formable. Typical applications include radiators, heat exchangers and beverage-can bodies.

The 4xxx series alloys exhibit a relatively low melting point and find use as welding wire.

The 5xxx series alloys find use in consumer electronic cases (strength, appearance and anodizing) and automotive structural components. Since this series of alloys is not heattreatable, any beneficial strengthening from cold working may be lost if the final part is subjected to a paint-bake cycle.

The 6xxx series alloys provide relatively good formability and will strengthen during the paint-bake cycle, making them useful for automotive body panels and closures.

The 7xxx series alloys are high-strength heattreatable grades that are not easily joined by commercial welding processes, so they are routinely joined by riveting.