1996-1999 Local strikes over local issues

1998 GM Flint strike: 54 days.

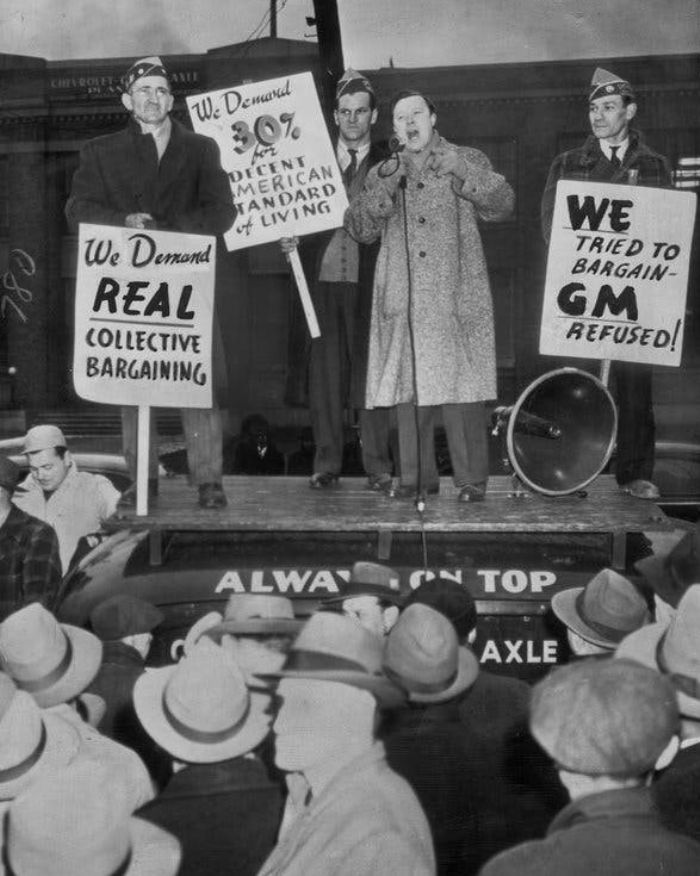

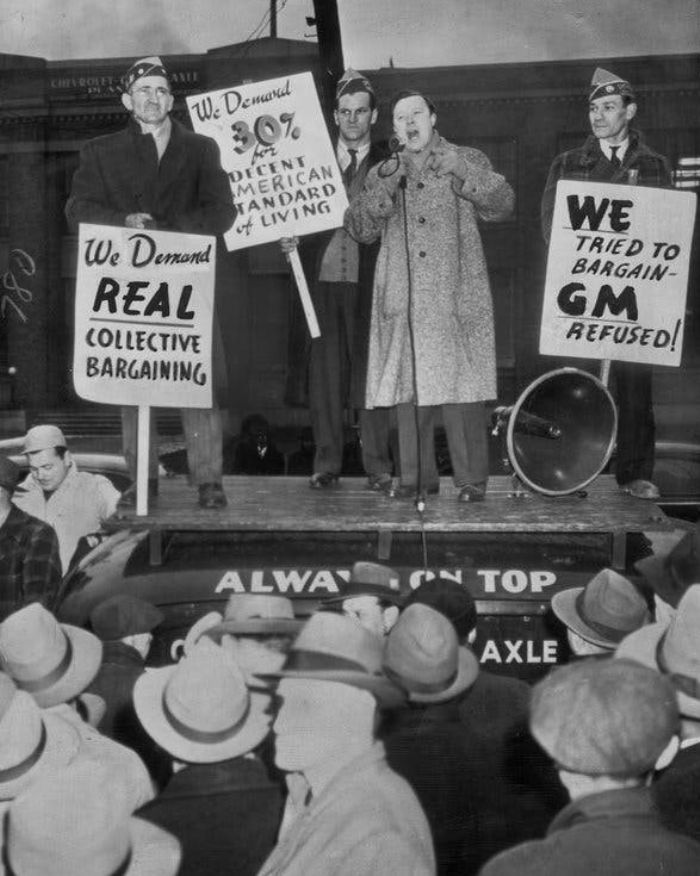

During World War II, there was labor peace with the UAW as the country focused on the war effort. In 1945, the UAW struck GM for 113 days; 320,000 workers were idled, asking for a 30-percent wage increase. Walter Reuther was UAW president at the time. The strike was considered a failure as employees received only a $0.18/hr. raise, but Reuther’s aggressive bargaining led to his being elected union president.

During World War II, there was labor peace with the UAW as the country focused on the war effort. In 1945, the UAW struck GM for 113 days; 320,000 workers were idled, asking for a 30-percent wage increase. Walter Reuther was UAW president at the time. The strike was considered a failure as employees received only a $0.18/hr. raise, but Reuther’s aggressive bargaining led to his being elected union president.

Pension Benefits, COLA, and More

In 1950, the UAW struck Chrysler over pension benefits, after winning a contract with Ford that included an agreement to pay the entire cost of pensions for workers with 30 yr. of seniority, at $100/mo.

Chrysler agreed to the amount but would not agree to fully fund it and

the strike lasted for 104 days, until the company caved. I was 2 yr. old at the time and my father was

an hourly worker at the Chrysler Jefferson Avenue plant. When his savings dried up, he left Chrysler

and the UAW and pursued a job outside of the auto industry. I still remember meeting him at the picket

line and what it did to our family.

Between 1950 and 1967 the UAW used Ford in establishing union

contracts. The 1967 Ford strike lasted

68 days, and it proved significant as workers won job security for higher-seniority

workers. The contract guaranteed workers

with at least 7 yr. of seniority 95-percent of their pay for a full year if

laid off. Workers also received wage

increases from $0.39/hr. to $0.54/hr. for unskilled labor, and $0.84/hr. for

skilled workers. The contract limited

COLA increases to $0.08/hr. paid annually instead of quarterly, which would

become the major issue in the GM strike of 1970. The strike cost Ford 500,000 vehicles and was

the longest national strike against Ford.

In 1970, under new UAW president Leonard Woodcock, GM

became the strike target. The main

issues selected by the UAW: a bigger wage increase, restoration of the cost-of-living

formula, and a 30- and-out retirement plan.

Cost of living was the key issue for the union, and while COLA had been fairly flat over time while inflation had peaked in the late 1960s. The average COLA was $0.26/hr., vs. the $0.08/hr. in the existing contract. GM CEO James Roche set his company’s positions, arguing that GM faced the highest interest rates since the Civil War, along with rising wages and raw-material costs, and declining productivity due to 13.3-million labor hours lost to unauthorized local strikes. GM’s data indicated that while it was still profitable, the company’s sales, profitability and cash dividends all had fallen sharply since 1965.

The 1970 strike proved devastating to both the UAW and GM. The average union worker received strike

benefits from the union of $30 to $40/wk.

According to GM, the strike cost it $90M in sales/day, in part because

it delayed the launch of the newly designed Chevy Vega, which GM positioned as

a competitor to the smaller Japanese imports.

The ripple effects were enormous, especially to the 39,000 companies supplying

GM with products and services, causing suppliers to lay off thousands of

workers.

As a salaried

employee at Chevrolet Detroit Gear and Axle at that time, I recall that about

three weeks into the strike, our HR department called us in the night before a

big picketing demonstration was to take place at the plant, to meet in the

salaried-employee parking lot and effectively march into the plant

together. As we walked toward the plant,

we were met by a large contingent of union strikers and deferred to their

suggestion that we go home.

Healthy Wage

Increases in the Face of Foreign Competition

The national settlement to the 1970 strike provided the

UAW with several concessions. Prior to

the 1970 strike, their average wage was approximately $4.03/hr. The new contract increased wages by 18

percent over 3 yr. Note: In rough terms, with a $1.74/hr. increase

over 3 yr. and 68 days of lost wages and a $40/wk. strike fund, the average

worker lost $800 during the strike. The union also persuaded GM to drop demands limiting the number of grievances a worker could submit, and permitted local union officers to spend time on UAW issues during company time. And the union won the elimination of the COLA cap while avoiding company-requested productivity gains.

The 1970s also saw stepped-up competition from Europe and Japan, changing the landscape of bargaining power and UAW membership. GM’s market share dropped from 50 percent in the 1960s to 31 percent in the 1990s. It missed the small-car boom in the ‘70s and the large-car boom in the ‘80s. Since the 1970s, GM had cut 50 percent of its workforce but still needed to pare 30,000 more workers in the ‘90s to stay competitive. Also, during the ‘90s the UAW switched its focus to striking key plants to damage GM’s revenue, while not overly shrinking the strike fund. A 17-day strike at two Ohio brake plants cost GM $900M in lost revenue and paralyzed its North American operations.

Health and Safety Concerns, or Investment Strategy?

The next significant strike came in 1998, a 54-day strike

by 3400 workers at the GM Flint metal center stamping plant; 5800 workers joined

them a week later at the Flint East assembly plant. Again, a new UAW president with an activist

bent, Stephen Yokich, was leading the UAW.

The strike was called to protest staffing and worker health-and-safety

concerns, as well as perceived failures by management to fulfill its pledge to

invest $300M in plant upgrades.

The Flint strikes stopped production at nearly 30 GM assembly plants and 100 parts plants across North America. Approximately 190,000 employees were laid off and the non-striking employees were eligible to collect unemployment benefits. The UAW paid about $120/wk. in health- and life-insurance premiums for striking workers, on top of the $150 weekly strike pay. GM claimed the strike was illegal since it was not over work rules but over GM’s long-term investment strategy, seeking to shift the company’s global investment strategy. The eventual GM-UAW agreement resulted in a GM promise not to close several of the striking factories, and to invest $180M in new equipment in one of its plants. UAW workers agreed to new work rules, including a 15-percent increase in the required daily output of parts for some workers.

The strike cost GM $2-billion in profits, and while in

the 1970s GM employed 78,000 people in the Flint area, the 1998 strike

effectively led to the closure of GM Flint facilities and the layoff of 7500

employees. At the time of the strike, I was working as a vice president of a

privately owned Canadian stamping supplier.

Our company was one of several engaged in a factoring setup for improved

accounts-payable payment time, fostered by GM with GE Capital. During the strike, GM cancelled the program and

our company was subjected to an extreme cash-flow issue. The strike not only

destroyed the GM connection with Flint but also laid the groundwork for our

company to eventually enter the Canadian equivalent of Chapter 11.

A 2009 Quickie, and Here We Are Today

In 2009, around the time of the great recession, a short two-day strike led to an agreement between the automakers and UAW that featured benefit-rule changes to assist in keeping the automakers afloat. And that brings us to the current situation, where, again, the UAW has a new, first-year activist leader, Shawn Fain. Fain has announced goals for negotiations at all of the Big Three, setting a collision course toward strikes at all three companies oncethe contract expired on September 14. Breaking with past practice, the UAW did not shake hands with management reps to begin negotiations and already has filed grievances with the NLRB over GM and Stellantis negotiations. Fain said, “If we have to strike to win economic and social justice, we will.”

The UAW is demanding raises more than seven times what

the union won in its 2019 contract negotiations, as well as a 32-hr. work week (for

40 hr. of pay), and a host of other gains.

According to Automotive News, there are four key economic issues

in play: tiered wages, use of temporary workers, COLA, and reinstatement of

pensions. The publication recently released

specifics of the Ford offer, which includes a 9-percent pay raise over the 4-yr.

contract, with bonuses that could increase pay by another 15 percent, permitting

workers to see annual earnings rise to $92,000 in the first year of the

contract from an average of $78,000 in 2022, including overtime and lump

sums. Workers also would receive $38,000

worth of healthcare and other benefits.

Ford also has offered to reduce the period required to reach full

seniority from 8 yr. to 6 yr. The union has rejected the offer, demanding a 46-percent

wage increase in 90 days, without tiers, and pay increases to match inflation.

It also wants more paid time off, return of the jobs bank for laid-off workers,

and a return to defined-benefit pensions.

Impact on Suppliers

What does this mean for suppliers? Metal forming suppliers to the Big Three can

take specific actions to protect their businesses. As I said, my company took a

serious hit in 1998 from the GM strike, which eventually resulted in the sale

of the business.

Most importantly: Cash is king. Suppliers should perform a 13-wk. cash-flow

analysis and cut back on non-essential expenditures. They need to maintain close communications

with their customers on the needs of the business, projected ordering plans

when production resumes after contract settlement, and they must understand the

impact on the supply chain of product coming from overseas.

In the August 25 issue of the PMA Pulse newsletter, UHY’s Tom Alongi presented additional strategies required to navigate and survive the potential strikes. In addition to preparing the 13-wk. cash-flow analysis, Alongi suggests that suppliers prepare scenarios with tiered layoffs; look to defer payables; prepare an inventory analysis of what can be done to move slow-moving excess inventory, to raise cash; and conduct a full-court press on collecting receivables. Suppliers should be reviewing significant contracts with counsel to be conversant on legal risks.

From a strategic perspective, review costing models, supply-chain support, and company strategy to keep employees aligned on the path forward. MF

Technologies: Management

During World War II, there was labor peace with the UAW as the country focused on the war effort. In 1945, the UAW struck GM for 113 days; 320,000 workers were idled, asking for a 30-percent wage increase. Walter Reuther was UAW president at the time. The strike was considered a failure as employees received only a $0.18/hr. raise, but Reuther’s aggressive bargaining led to his being elected union president.

During World War II, there was labor peace with the UAW as the country focused on the war effort. In 1945, the UAW struck GM for 113 days; 320,000 workers were idled, asking for a 30-percent wage increase. Walter Reuther was UAW president at the time. The strike was considered a failure as employees received only a $0.18/hr. raise, but Reuther’s aggressive bargaining led to his being elected union president.