Dos and Don'ts of Mass Finishing

April 1, 2016Comments

Follow these tips to optimize your surface-finishing operations.

Mass finishing as a mechanical surface-finishing method has been around since the mid-1950s. But because it is a largely empirical process, mass finishing is still one of the least-understood, under-appreciated manufacturing technologies. Many manufacturing engineers still consider mass finishing as low-tech, and pay little attention to properly setting up and optimizing their surface-finishing operations. The results usually are higher overall finishing costs, higher scrap rates and a lot of unnecessary rework. Don’t make those mistakes.

More Than Meets the Eye

|

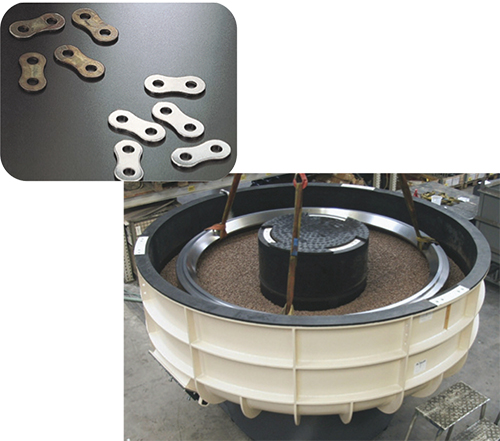

| Figs. 1 and 2—Finishing of parts such as small chain links (above) requires only a small finishing machine, but large parts, such as bearing rings with diameters greater than 100 in. (right), require finishing in large rotary vibratory machines. |

The first mass-finishing vibratory machines were used exclusively for simple deburring operations on mass-produced parts, mainly in the automobile industry. In the beginning no one thought about defined edge-radiusing, precise surface-roughness readings, pre-plate finishes or mirror-image polishing. Today, mass-finishing systems can produce practically any surface finish, from simple deburring to high-gloss polishing, on practically any kind of workpiece.

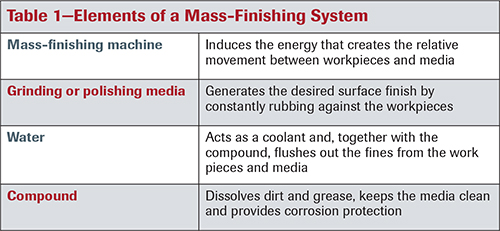

Yet for many, mass finishing remains a vibratory bowl filled with some “rocks.” Not true. It embodies a complex system with multiple elements that must be perfectly matched to each other (see Table 1). Only the ideal matchup of these elements guarantees ideal finishing results.

Workpieces Drive Finishing Solution

Any surface-finishing solution evolves around the workpieces. Their material type, size, shape and above all, the finishing objectives, determine what type of finishing process must be selected.

Workpiece size is especially important. For example, the deburring and edge-radiusing of small stampings, such as chain links (Fig. 1), can take place in a small, high-energy machine with a capacity of less than 1 cu. ft. On the other hand, the polishing of large wind-power gears weighing to 5 tons requires a significantly larger machine (Fig. 2) with capacities of well over 100 cu. ft.

|

| Fig. 3—Delicate parts, like the artificial knee joints shown here, must mount to fixtures to prevent scratches and nicks. |

Fragility of the workpieces is another important factor. With delicate, high-value workpieces, part-on-part contact must be avoided to prevent scratches or nicks (Fig. 3). Typically, these types of workpieces mount to a fixture that prevents any part-on-part contact during finishing.

Workpiece shape influences media selection. Parts with complex geometries and internal passages may require completely different media shapes and sizes compared to simple forgings.

And finally, workpiece material plays a role as well. For instance, parts made from aluminum or magnesium typically must be processed with less-abrasive media, while hard-to-machine metals such as titanium require a more aggressive treatment.

And finally, workpiece material plays a role as well. For instance, parts made from aluminum or magnesium typically must be processed with less-abrasive media, while hard-to-machine metals such as titanium require a more aggressive treatment.

Processing Trials Yield Optimal Finishing System

Of course, selecting the right machine, media and compound can be a bit intimidating. Not only must shops choose among a variety of machine types and sizes, they must also pick the right media from hundreds of types, shapes and sizes. And, they must select the right compound, and ensure that the process water is not too hard or too soft.

|

| Fig. 4—All major mass-finishing-equipment suppliers maintain test labs, such as Rosler Metal Finishing USA’s lab in Battle Creek, MI (right), where they can run processing trials with a customer’s workpieces to develop the optimum finishing process and choose the right combinations of equipment and consumables. |

That’s why the choice of machine, media and compound should be left to the experts. All major mass-finishing-equipment suppliers maintain test labs where they can run processing trials with a customer’s workpieces to develop the optimum finishing process (Fig. 4), and choose the right equipment and consumables.

Considering the fact that mass finishing is highly empirical technology offering hundreds of equipment, media and compound combinations, it is not surprising that more than 95 percent of all equipment sales are preceded by processing trials at the equipment suppliers.

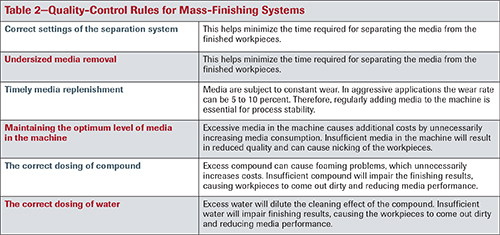

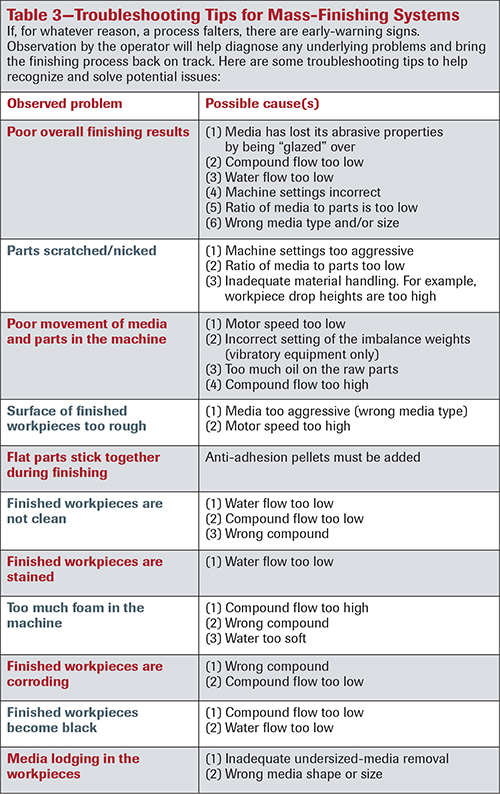

Once a mass-finishing process has been established with the selection of machine, media and compound, the system must be constantly monitored and, of course, properly maintained. By following a few simple quality-control rules (see Table 2), the process will remain stable, producing the desired finishing results. If needed, Table 3 offers helpful troubleshooting tips.

MFArticle provided by Rosler Metal Finishing USA, LLC, Battle Creek, MI; 269/441-3000; www.rosler.us.

See also: Rosler Metal Finishing USA, LLC

Technologies: Finishing

Comments

Must be logged in to post a comment. Sign in or Create an Account

There are no comments posted. Finishing

FinishingCompletely Biodegradable and Recyclable Corrosion-Inhibiting...

Monday, June 2, 2025

Finishing

FinishingWhy Automated Deburring Works in Fabrication

Lou Kren Thursday, March 30, 2023

Finishing

FinishingAutomated Orbital Wrapper Eliminates Pallet-Wrapping Bottlen...

Thursday, March 16, 2023