What Good is a Good Stamping

December 1, 2014Comments

...if it arrives at the customer dinged and damaged? Making sure that doesnt happen falls on the shoulders of Advanta Industries, a manufacturer of returnable racks and dunnage. Recently, the fabricator and weld-shop extraordinaire added some weapons to its arsenal: laser-cutting machines.

|

| Two Amada ASLUL automatic load-unload systems (far right) deliver blanks to and receive nested, cut material from a 4-kW fiber-laser cutting machine at Advanta Industries. Move 130 ft. to the left (just out of frame) and you’ll find a single ASLUL system that automates material flow to and from an Amada CO2 laser-cutting machine. |

Usually I’m writing about stamped and fabricated parts and assemblies, and the technology that makes it easier for metalformers to optimize quality and productivity. With this fabrication-shop visit, rather than learning how companies can make better parts, I’m learning how they can protect those valuable parts in transit. More specifically, how the part racks and shipping containers are manufactured to protect their valuable cargo, such as stamped and fabricated metal parts and assemblies.

As explained by Michael Grams, CFO of returnable-rack and dunnage manufacturer Advanta Industries, “the time crunch that affects nearly every automotive program hits us harder than any other supplier in the chain. As projects face delay after delay, by the time designs are finalized, for new automotive stampings for example, we might have just a few weeks to design and fabricate the returnable racks used to transport them. We’re the last step in the process, and we can’t work on the racks until the part designs are finalized and the suppliers figure out how they’re going to ship the parts.”

|

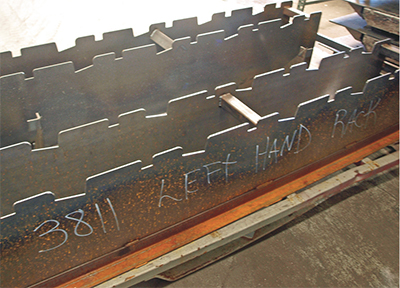

| Along with improved accuracy and cut-edge quality—when comparing plasma to laser cutting—is the ability to common-line cut. “We do it all the time,” says Advanta production manager Rusty Obermyer. “With just this one sheet (right), common-line cutting saves more than 30 ft. of cutting.” |

And that’s just one challenge Advanta, based in Petersburg, MI, and with two new plants recently opened in South Carolina, faces. Another noted by Grams: Racks and other dunnage products have evolved, due to specific market forces, into precisely engineered and fabricated products. Those market forces include the trend toward automated (robotic) part handling, and the escalating surface-finish requirements of automotive parts.

“Robotic unloading means we have to be more precise than ever with part location and orientation within the racks,” explains production manager Rusty Obermyer. “Our manufacturing tolerances have really been squeezed in the last few years. We’re frequently tasked with cutting parts and providing welded assemblies with ±0.005-in. dimensional tolerances.”

Better Fixtures Beget Better Racks

Precision to Obermyer and Grams means laser cutting of the sheet and plate components used to manufacture its products, as well as the components making up its precision weld fixtures—a huge part of its business. For Advanta, the mission is designing better racks that not only protect their precious cargo, but also allow customers to fit more parts into them. This allows customers to save significantly on freight costs over the life of a program.

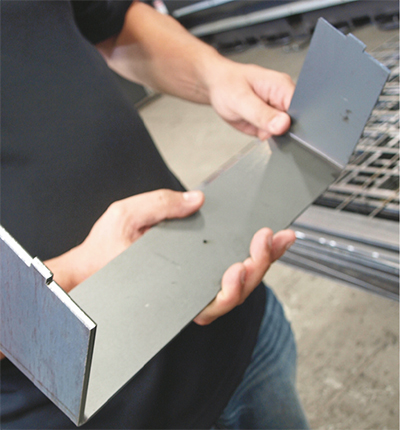

The better the weld fixture the better the rack, and we spied some amazingly designed and built weld fixtures when touring the 130,000-sq.-ft. Advanta shop. Precision-laser-cut parts fit together beautifully in the fixtures to help welders assemble the racks. It’s clear that their jobs are made that much easier—meaning faster and with less chance for error—when weld fixtures are built from precision-laser-cut components.

The workhorse cutting machines at Advanta: an Amada FOM2 machine with a 4000-W CO2 laser, added in 2012; and an Amada FOL3015AJ machine with a 4000-W fiber laser, brought into the shop in 2013 direct from the FABTECH floor in Las Vegas. Automated material-handling systems manage material flow for both machines—twin storage towers (Amada ALSUL models) rack raw material and completed work at the fiber laser, and a single ALSUL tower manages material for and from the CO2 machine.

Bringing Laser Cutting Inhouse

“We outsourced laser cutting for several years,” says Grams, “and we also had a high-definition plasma-cutting machine inhouse for a couple of years. Bringing laser cutting inhouse made sense to us when we took a closer look at our outsourcing costs; when we realized we could decrease lead times by eliminating the delays that accompany outsourcing; and when we recognized the growing trend toward precision cutting.”

An added benefit of bringing laser cutting inhouse is the extra opportunity for engineers and designers to find creative ways to leverage the technology to improve the fabrication processes. Case in point: Using the lasers to cut tabs and slots into rack components to make assembly more efficient and error-proof—in many cases, significantly more efficient.

“We can cut different sizes of tabs and slots in parts so that there is only one way to assemble,” says Obermyer. “That allows our welders to focus on what they do best—weld—and worry less about assembly and fitup. The parts fit together snugly with minimum joint gaps.”

Unattended, Lights Out

Advanta runs both Amada machines unmanned for two shifts, and lights-out during a third shift. Longer-running jobs (often thicker plate) typically run lights-out. Each material-storage tower comprises nine shelves rated to 6600 lb. of material. The automated material-handling systems deliver nested blanks from the towers to the lasers, and return cut blanks back to the storage towers to be manually shaken apart later.

Advanta fabricates primarily mild-steel sheet and plate, as well as square tube, from 16 gauge to 1 in. thick; the sweet spot is 3⁄16 in. material, which runs on either the CO2 or fiber-laser machine. Thinner work routes to the fiber, which cuts with shop air up to 14 gauge and oxygen on thicker work; for the occasional galvanized-steel job, nitrogen gets the call. Work 3⁄16 in. and thicker routes to the CO2 machine, using oxygen as the assist gas.

“Cutting 14-gauge steel using shop air on the fiber laser is amazingly fast,” says Obermyer, “up to 750 in./min. That’s four times faster than with the CO2 machine.”

Obermyer has learned a lot in a short time when it comes to optimizing laser-cutting parameters to achieve certain quality and productivity goals. For example, he describes a recent job cutting trailer-hitch side plates from thick steel, originally specified as 3⁄8 in. but that ultimately wound up being cut from 0.390 in. work (or 0.015 in. thinner).

“You wouldn’t think that the 0.015 in. would make a difference in the laser-cutting process,” he says, “but it definitely did. While we were able to cut the slightly thinner material a little faster, when we increased gas pressure the cut edge started to get choppy. So we actually reduced gas pressure a bit and increased the pulse rate of the laser, which made for a beautifully smooth cut edge.” MFView Glossary of Metalforming Terms

See also: Amada North America, Inc

Technologies: Cutting