The Basics of Coil Processing Equipment, Part 2: Straightening the Coil

June 1, 2012Comments

In part one of this series (January 2012 issue) on coil-processing equipment, we covered unwinding the coil. Here we focus on material straightening, to allow the sheet to pass freely through the die.

The purpose of straightening in a typical coil-feed line is to prepare the material to allow it to pass freely through the die and produce acceptable parts. Requirements vary depending on any material defects, the design of the die and finished-part requirements. Straightening is accomplished by bending the strip around sets of rollers that alternately stretch and compress the strip’s upper and lower surfaces, exceeding material yield point so that both surfaces end up the same length after springback. The result: flat material.

Types of Straightening Machines

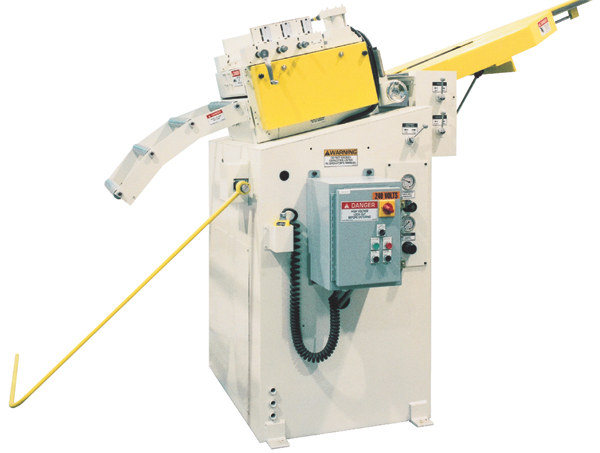

Straightening machines fall into two basic categories—straighteners (or flatteners) and corrective levelers. Straighteners typically operate five to 11 work rolls whose diameter and center distances vary depending on workpiece-material thickness and width. Generally, rollers are fairly large in diameter, widely spaced and not backed up. Straighteners will remove coil set from the material, allowing it to pass unrestricted through the die and satisfying most applications.

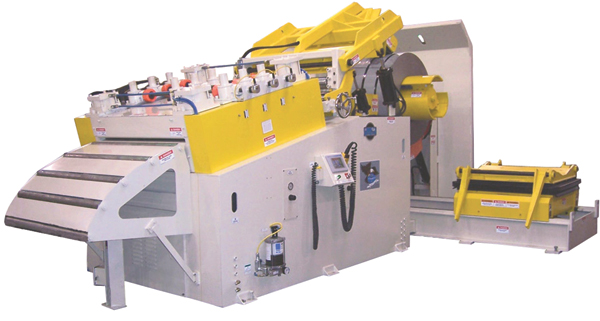

Corrective levelers will remove not only coil set but also camber, wavy edges, center buckles and trapped stresses within the material, so that it will stay flat after processing through a die. These machines are distinguished by small-diameter closely spaced rolls—with backups—and the ability to flex the rolls. They normally have a greater number of work rolls than conventional straighteners, and since they work the material much harder and their rolls can be flexed, precision levelers als are powered. Therefore, they require more powerful drives than do straighteners.

With pull-through straighteners, horsepower must be drawn from the feeder. This can either reduce its speed capability or greatly increase cost. Additional disadvantages to pull-through straighteners include material marking, should the nonpowered straightening rolls slip on the material during starts and stops; and inaccuracy from feed slippage, due to the additional load.

Power straighteners or levelers can be configured as part of the unwinder, as in the case of coil cradles, or for pull-off operation with coil reels. They also can be free standing with a second slack loop between the straightener and unwinder—as with pallet decoilers or in cases where delicate material would be damaged by pulling off of a large coil. In most cases, a slack loop follows a powered model, which allows continuous operation without starting and stopping. This reduces power requirements relative to combination feeder/straighteners, which straighten material as it feeds and are required to start and stop with each feed progression.

Principles of Straightening

In theory, three staggered rolls should be sufficient to straighten most materials. This basic approach can be applied if the amount of coil set in the material remains constant throughout the coil. However, coil set can dramatically increase as the coil is depleted, depending on material thickness, composition and yield strength.

In most cases, coil set is induced in the material during a previous process, such as slitting, edge conditioning or finishing. The coil’s wraps are placed under tension and compression as the material bends around the outside diameter of the coil. Coil OD typically is 54 to 72 in., while the diameter of inner wraps around the inside diameter of the coil typically measures 16 to 24 in. This potentially large difference can result in a dramatic change in the amount of coil set in the material. With only three staggered rolls, the operator would have to constantly adjust the straightening machine to obtain an acceptable level of flatness.

Therefore, power straighteners are built with multiple work rolls to effectively address the issue of varying coil set. The more work the greater the ability to remove coil set.

Another basic principle of straightening: Thicker materials require fewer and relatively large-diameter rolls, with greater spacing between them. As material thickness increases, roll diameter and support-journal diameter must increase. Also, the work rolls must be able to withstand the forces required to back-bend the material without excessive deflection across their width.

Thinner materials will require a greater number of relatively smaller-diameter rolls, with spacing relatively short to effectively stretch and compress the material. On light-gauge material, consideration must be given to the support-journal diameter of the work rolls. As the width of the material and machine increases, so does the tendency for the smaller-diameter rolls to flex and deflect. This deflection of the straightening roll or journals can lead to material defects such as wavy edges, and machine problems such as broken journals and excessive gear wear.