In 2008 (effective January 1, 2009), President Bush signed into law the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA). The ADAAA has changed how we interpret the above criteria to determine whether or not a person has a disability.

In this column, we will focus on how the ADAAA has changed how the ADA views whether or not a person has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the person’s major life activities.

What does it mean to have an impairment that substantially limits a major life activity? The U.S. Supreme Court attempted to answer this question in the past 10 years in two major cases.

In 1999, the court heard a case called Sutton v. United Airlines. In this case, the court ruled that whether or not a person is substantially limited from engaging in a life activity must take into account available measures to correct or mitigate the underlying impairment. So, for example, if a person could perform a major life activity so long as the person is on medication, that person would not be disabled since there are corrective measures available.

Three years later, the court heard a case called Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Kentucky, Inc. v. Williams (a case we previously wrote about in this column). In this case, the court ruled that in order to be substantially limited in a major life activity, “an individual must have an impairment that prevents or severely restricts the individual from doing activities that are of central importance to most people’s daily lives.” In accordance with this ruling, an employee-plaintiff must show that he is completely unable to perform or severely restricted from performing a major life activity.

The combination of these two cases put a very high qualification threshold on plaintiff-employees, making a case for disability extremely difficult to prove. It did not help that “major life activity” is itself a relatively vague term, not otherwise defined under the ADA.

These two cases have been considered to be excessively restrictive and not consistent with the legislative intent of the ADA. The solution? The ADAAA.

The ADAAA overturns the rulings of these two cases and provides some new guidance to determine whether or not a person has an impairment that substantially limits a major life activity.

First, what is a major life activity? Before the ADAAA, the ADA did not address this. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) came out with a list of major life activities. The list includes caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning and working. The ADAAA adds many items to this list, such as eating, sleeping, standing, lifting, bending, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating and major bodily functions (such as immune system, normal cell growth, digestive, bowel, bladder, neurological, brain, respiratory, circulatory, endocrine and reproductive).

Now that we have a better idea of what comprises a major life activity, do we know when such an activity would be substantially limited? Well, not yet. What we do know is that the ADAAA rejects the unable-to-perform, significantly restricted threshold and requires the EEOC to develop new regulations. We do not yet know what these new regulations are, but the ADAAA specifically calls for them to be less stringent than they have been.

Lastly, in direct contrast to Sutton, the ADAAA states that corrective or mitigating measures no longer may be considered. No longer are aids such as medicine, medical supplies or equipment, prosthetics, assistive technology, reasonable accommodations or adaptive neurological modifications a factor. Instead, it is the underlying impairment that must be examined in an “unmitigated state.” There is, however, one notable exception: corrective lenses (eyeglasses and contact lenses).

Next month, we will look at how the ADAAA has changed how a person is regarded as having an impairment. MF

This article provides only general information about complex labor laws. It should not be considered as a legal opinion or legal advice. We strongly recommend that readers confer with legal counsel on the application of the law to their individual situations and the use or modification of this article.

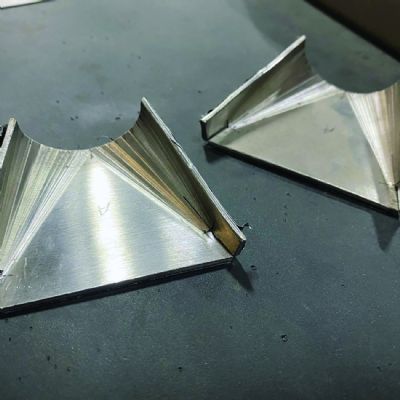

Technologies: Bending