Helper and the rest of the research team worked closely with the Precision Metalforming Association (PMA) to develop trade-specific survey questions and ensure that stampers were well represented in the study. “The contribution of PMA and its members to the study was tremendous,” says Helper.

The team notes throughout the study that firms, based on the data collected, generally can be categorized into four groups, representing four basic paths to success:

- Engineering-intensive firms, employing a high percentage of engineers and which profit from a focus on research and development;

- Craft-skill firms, paying competitive wages for highly skilled workers and which often participate in the tooling industry, while demonstrating below-average rates of formal process-improvement initiatives;

- Clever cost-cutter firms, which tend to pay lower wages for low- or semiskilled labor yet often describe practical or creative solutions that help avoid the need to spend money; or

- Kaizen firms, which pay moderate wages and are most likely to pursue Toyota-style management philosophies to optimize flexibility, serve multiple markets and institutionalize continuous-improvement practices.

The survey is unique in that it captures a multifaceted view of each firm. Customer relations, product development, workforce development, financial and operational issues are studied, so that the result is a textured understanding of the complex reality facing supply-chain firms. The intent is that this information can be used by decision makers at supplier and customer firms, as well as in government, to understand the specific challenges that individual firms face, and the overall challenges that threaten the health of the automotive supply chain as a whole.

Possible Futures: Collaborative

The research uncovers evidence of two possible futures for America’s automotive industry. One is characterized by long-term collaborative relationships between firms at all tiers. In this model, customers and suppliers work together on (and benefit together from) product development, cost savings or other trans-tier issues.

“With foresight and long-term thinking,” say the survey’s authors, “some firms have completely revamped their strategies for profitability, adding value to products instead of simply cutting costs...finding that they fare better when they can link their product strategy, manufacturing process and workforce development strategy in a that allows them flexible or agile production.”

Fig. 2

Such a business model allows manufacturers to outperform competitors in quality, problem solving and just-in-time production and delivery. “The result can be larger profit margins for the firm and higher wages for workers,” the survey finds.

The study also reveals that “the recession increased the prevalence of collaborative relationships.” An interesting trend: In 2007, 32.2 percent of suppliers believed that their customer would help them match a competitor’s efforts to provide a similar product at a lower cost; that percentage jumped to 41.5 percent in 2011. Apparently, “the recession taught firms that they are more likely to survive if they work together to reduce costs,” the survey notes.

...or Combative

The second possible path is one that is familiar to many stampers. It is characterized by fickle and antagonistic relationships, margin squeezing and the inability to invest in equipment, new technology, innovation or people. This path is a recipe for industry-wide stagnation and the declining relevance of American manufacturing. The study finds that large segments of the automotive supply chain are characterized by each of these two scenarios, demonstrating certain elements of both.

While supplier firms cannot dictate the culture of current and potential customers, to a degree, they can choose who they work for. Interviews yielded interesting stories of firms turning down work in the middle of a recession, refusing terms or even firing major customers. As one executive relayed, his “top-line number may have shrunk (by 40 percent), but the bottom line grew overnight by getting rid of that pain-in-the-butt customer.” Many firms reported very positive relations with their customers, so options are out there.

Strategies for survival are not limited to external relations, however. The data shows that certain inhouse practices are frequently adopted together. Helper calls one such grouping “high road” practices, which includes worker training and investment, empowerment at all job levels, and continuous-improvement practices. Such firms experienced 10.9-percent less sales loss during the crisis.

Fig. 3

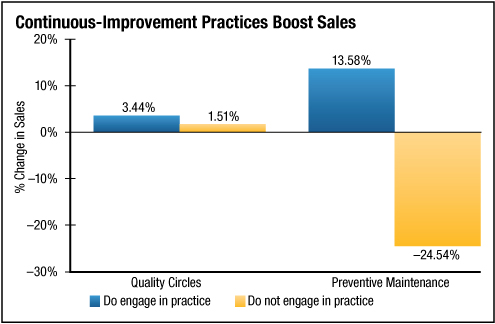

Fig. 1 shows the responses of metal stampers to questions regarding specific continuous-improvement practices, including formal employee involvement via quality circles and formal preventive maintenance in relation to sales.

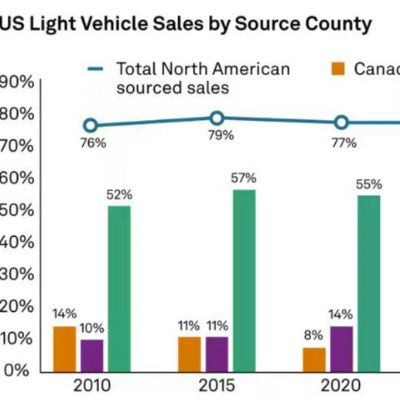

Fig. 2 shows how pervasive some continuous-improvement practices have become amongst stampers. In many firms, the study finds that process improvements are data driven, preventive-maintenance programs are in place and adhered to, and that a sense of teamwork pervades.

Distinctive and Systematic Strategies

The data further distinguishes two forms of the high-road strategies called out by Helper: Those that are “distinctive” and those that are “systematic.” Distinctive firms develop deep skill and novel products that are hard to imitate, whereas systematic production focuses on data collection to identify and eliminate sources of waste.

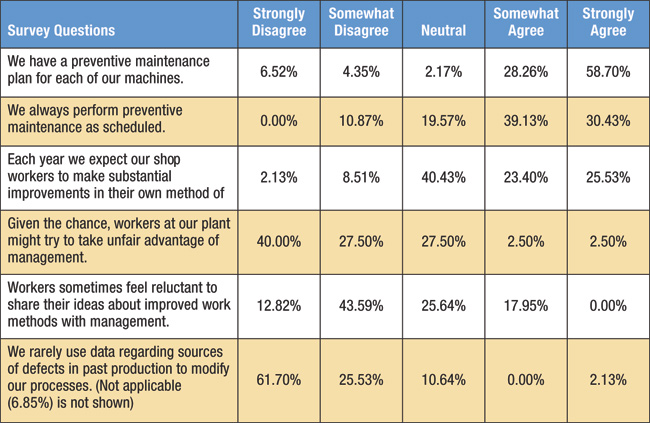

While combining the distinctive and systematic strategies is particularly effective, firms usually do not use both, and many firms do not pursue such practices at all. It is somewhat surprising that two-thirds of stamper-respondents have never implemented formal problem-solving teams, and interest may be falling (Fig. 3).

This certainly is due in part to customer purchasing strategies that deprive suppliers of the financial or organizational resources they would need to implement such practices. Increasingly since the 1980s, the supply base is a shared resource, with most suppliers serving various OEMs and higher-tiered firms. Customers want to do cost-shifting and get a free ride on investments made in their suppliers. They want the time and money to come from their competitors or the supplier firms themselves.

But what also is missing, according to Helper, is the kind of government support for manufacturing that is found elsewhere around the world. “Public policies do not do enough to pave the high road and block the low road,” Helper says. Furthermore, based in part on the transactional perspective of many purchasing departments and their incentive structures, there is no coordination of the supply chain as a whole system. That is, though individual customer firms may be unwilling to fund it, as a nation we collectively want manufacturing to be strong.

Strategies for Crisis Survival

The high road clearly represents a good strategy for the long run, and the best firms had already started down that road before the crisis. In contrast, while the cost-cutting, low-fixed-cost strategy did help some firms get through the crisis, it’s not a solid long-term strategy.

Workers with years of experience may never return to many of these firms. About two-thirds of firms surveyed chose to postpone investment in equipment, but eventually the phobia over investment will have to fade. The data shows that those who continued to invest in their processes, people and new-product and market development are faring better in the wake of the recession. MF

Technologies: Management, Materials

The project described here is a part of Driving Change, a research consortium of the Indiana, Michigan and Ohio Labor Market Information offices;

The project described here is a part of Driving Change, a research consortium of the Indiana, Michigan and Ohio Labor Market Information offices;