Muscle-Bound Coil Line Breathes New Life into Transfer Press

September 1, 2008Comments

Heavy-metal stamper Stamco Industries rejuvenates a 3000-ton transfer-press line used to stamp thick HSLA steel by installing a new, robust coil line. Downtime is down, press speed and throughput are up, as is press capacity--by 15 percent.

|

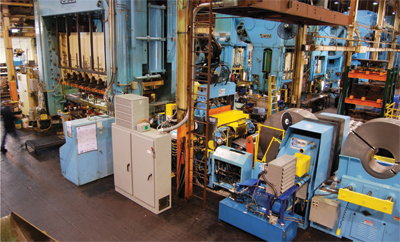

| Stamco’s new coil line, which requires only 17.5 ft. of floor space, feeds a 3000-ton Verson press with HSLA steel to 3⁄8 in. thick and 36 in. wide. |

Stamco Industries, Inc., Euclid, OH, has put in 25 years of hard labor providing customers in the automotive and heavy-truck market, in addition to others, with heavy-gauge stampings as well as a host of value-added services such as welding, machining, parts washing and assembly. In 1997 the company expanded its stamping capacity, to handle plate as thick as ¾ in., by installing a 3000-ton Verson press for transfer-die applications. To run progressive dies on the massive press, with high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels with yield strength to 50,000 psi, the firm added a feed unit to the press with straightener and coil cradle rated for material to 48 in. wide. For a few years, production on the press line ran smoothly, stamping housing covers, backing plates and other parts for the heavy trucking industry. Materials ranged from 1⁄4 to 3⁄8 in. thick, and in many cases the stampings weighed as much as 20 lb.

At the time, the feed system was considered heavy duty, more than capable of running the types of jobs required. But after some time, customers increasingly began specifying their parts be made of HSLA materials with 80,000-psi yield strength, which, according to Howard (Skip) Nieberding, Stamco’s special projects/safety manager, was approximately equivalent to stamping materials at double the thickness.

Also, a Stamco customer of brake components for Class A trucks requested that more of the parts run on the transfer press so that secondary piercing and forming operations could be performed under the single ram, rather than running the parts on a series of single-hit dies. It reduced the variety of part designs and restricted the quantity of part numbers, allowing Stamco to run larger volumes and justify moving the job to the transfer press. The move saved the customer money, but further strained the feed line.

“That’s when things started to not run so smoothly,” says Nieberding. “Our existing feed system, with pneumatic pinch rolls and a 40-hp drive, struggled to pull the 80,000-psi material. We experienced excessive wear and tear on the equipment, side guides were destroyed and the system could not dekink the trailing edge of the coiled material. This resulted in downtime with each coil of steel, as operators cut the end off with nibblers, a slow and hazardous operation.

“Yet, one of the most troubling aspects of the feed system,” Nieberding continues, “was its serviceability—admittedly we push our systems to their limits, and with the grueling work load we put on the rollers, the bearings needed replacement all too frequently. This process took as long as a week to complete, to remove the straightener head, disassemble the components and replace the bearings.”