Productivity Up, Material Consumption Down—What

Could be Better?

January 1, 2008 Rome Tool & Die stamps flatter parts, conserves material and enhances operator safety by installing a new coil-feeding system.

|

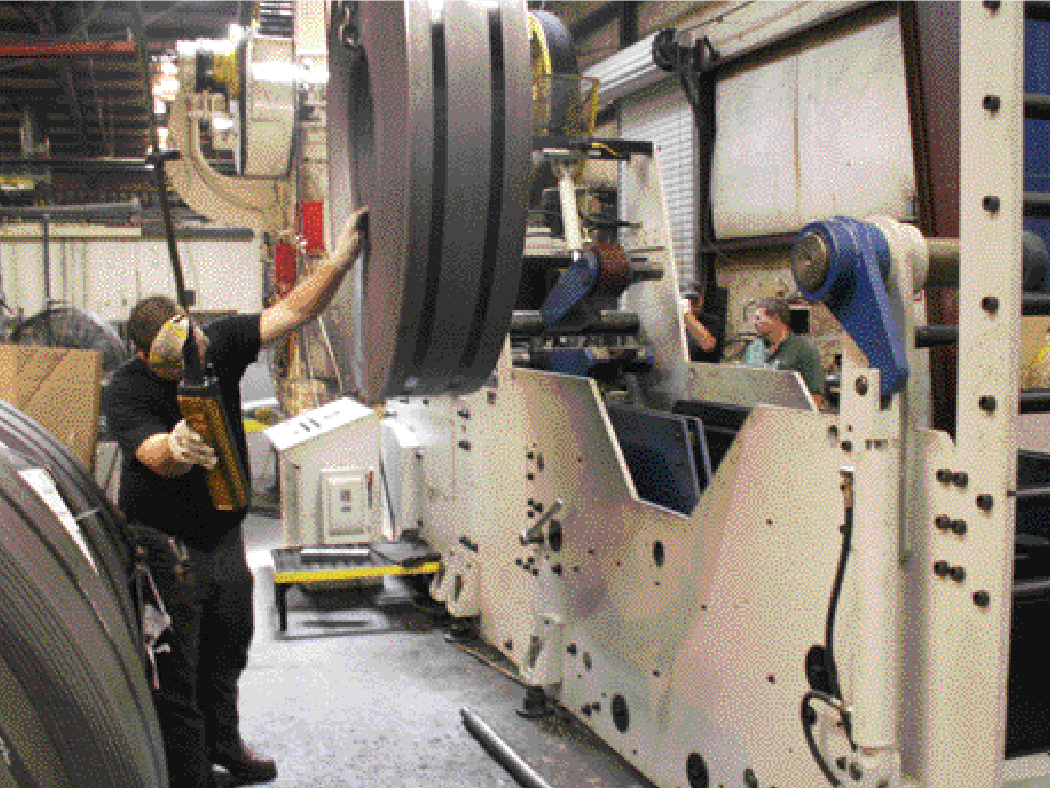

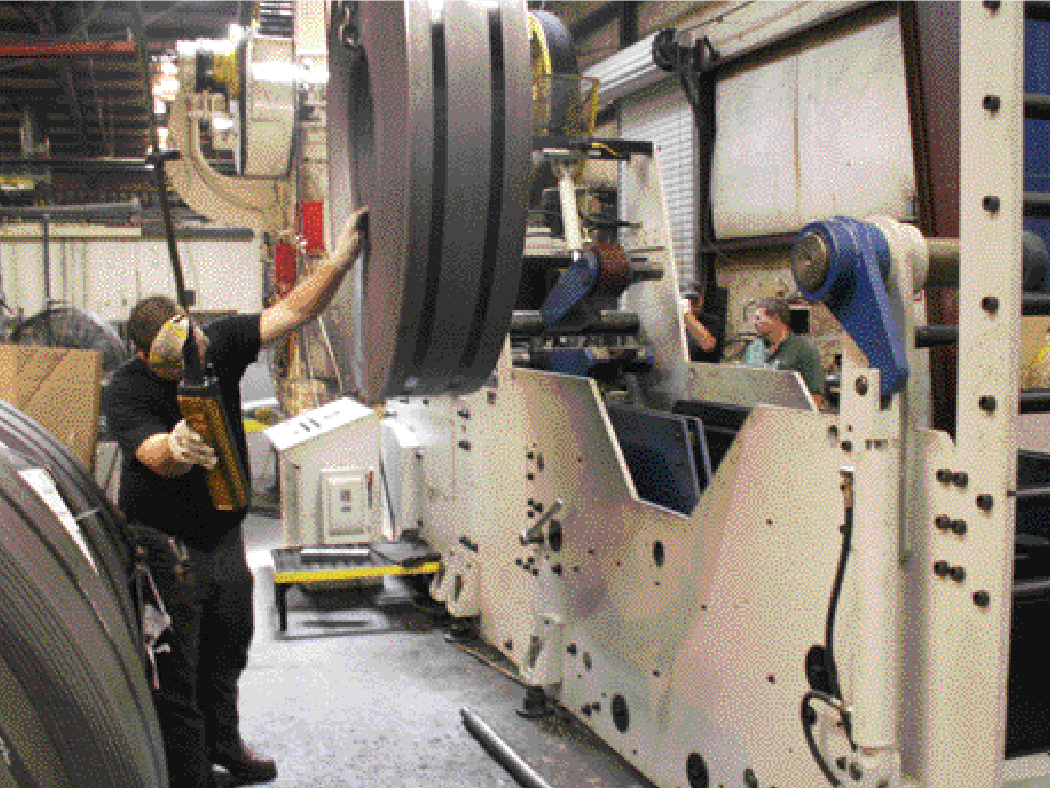

| Changeover times with a new coil line are faster—by 10 to 20 percent—and the overall operation is more convenient. And because workers no longer have to wrestle the ends of the coil with pry bars and hammers, changeover is safer than ever before. |

Effectively manufacturing heavy-duty brake shoes recently challenged contract stamper Rome Tool & Die (RTD), Rome, GA, to improve quality while at the same time eliminate secondary operations—doing so in a tight floor-space footprint on an old workhorse mechanical press.

RTD occupies a 140,000-sq.-ft. manufacturing facility where it performs stamping, forming and various finishing operations, in addition to turning, milling, grinding, heattreating, welding and assembly. Its Rome Heavy Duty (RHD) division, founded in 1979, produces more than 110 types of heavy-duty brake shoes. According to David Beckman, tool room/maintenance manager, “half of our business is contract stamping, mostly progressive die. The other half of our business is supplying heavy-duty brake shoes. We stamp shoes for tractor-trailers, bus brakes—anything in the heavy-duty line.”

Recently the firm installed a compact coil-feeding system, supplied by GSW Press Automation, represented by Coe Press Equipment, Sterling Heights, MI, on an existing press line to produce a brake-shoe rib component. An 800-ton single-point press stamps 5⁄16-in.-thick hot-rolled pickled and oiled steel, fed from 13-in.-wide coils on 3-in. progressions. Maximum capacity of the GSW line is 20-in.-wide material to 3⁄8 in. thick.

“This press line, dedicated to that one particular part,” Beckman says, “supports the production of 1.4 to 1.5 million brakes shoes per year, and most shoes have two ribs each. That means we stamp close to 3 million rib parts per year on this line. Right now, we are running two shifts. And, we definitely see that business increasing.”

Improved Flatness and More Usable Floor Space

Prior to installing the GSW system, the firm relied on a feed line with a servo feeder, a regular coil cradle and a straightener assembly. The new system takes up about two-thirds the floor space of the old line. “We saved about 8 ft. of space,” Beckman says. “That enabled us to get the feeding equipment out of the transport lane for the steel bay, which had been a tremendous logistics problem.

“We decided to replace the older feeding equipment with the new heavy-duty compact coil line primarily because we were looking to decrease coil change-over time, save material and provide better material flatness,” Beckman continues. “The new line avoids the use of a pit, which can actually reintroduce coil set. Instead, we now have flatter material feeding into the die, which in turn produces a flatter part. We’ve probably seen a 50- to 75-percent decrease in flatness issues. It’s not actually a reduction in scrap rate; it’s elimination of rework on those particular parts because of flatness issues. It’s hard to end up with a reject because we can restrike the part to correct flatness issues. What we actually save is the cost of that secondary operation, and that is a huge answer to our operational challenges.”

|

| The upgraded press line, dedicated to stamping brake-shoe ribs, supports the production of 1.4 to 1.5 million brakes shoes per year, and most shoes have two ribs each. That means the line yields close to 3 million ribs per year. |

Flatness used to be controlled partially by the equipment and partially by the grind profile of the punch that makes the part, according to Beckman. “Prior to installing the GSW line, we actually had to pull that die out from one lot number of steel to another and change the angles on some of those grinds in order to finish flattening the part using the tool itself,” he says. “We’re trying to maintain 0.020-in. total flatness. We were able to do it with the other equipment as I described, but now, with the new coil line, we can do most of that without pulling the tools and regrinding the punches, which was killing die life.”

Since each particular lot of steel can comprise anywhere from three to six coils, and typically the plant runs three coils per shift, or six coils per day, it was making that change as often as twice in a day, depending upon what batches of material and heat numbers came in. “Each maintenance cycle took 2 to 3 hr. to pull the tool and adjust the grind. We’re talking tens of thousands of dollars annually,” says Beckman.

Coil and Sheet Handling

Coil and Sheet Handling