Page 32 - MetalForming May 2011

P. 32

Digitizing

the Press-Brake Bending Process

For many years, the blanking and laser-cutting stages of the sheet- metal-fabrication process have advanced to realize the advantages of offline programming. However, many shops have been slower to adopt this practice for the more-complex 3D bending process.

As computing power has increased to handle the 3D models required to process folded shapes, fab-

ricators now can experience

the advantages of virtually processing their formed

parts. Fabricators working

in a low-volume high-mix production environment

can take advantage of

offline processing and enjoy

huge benefits in time, effi-

ciency and costs.

Opening the Box

Prior to the blanking

process, part data is imported

into computer-aided man-

ufacturing (CAM) software,

used by a programmer for

part processing on a specific machine. The program contains information on the tools required, as well as lines of code that the machine tool’s computer numerical controller (CNC) uses to process the part. This program down- loads directly to the machine (laser-cut- ting machine or turret punch press, for example) with tool-setup information. The machine operator needs to do little more than call up the required program, install tools according to the information

Scott Ottens in bending product manager, Amada America, Inc.: www.amada.com.

As more and more fabricators enter the arena

of low-volume high-mix production, they should look to take advantage of offline press-brake programming to enjoy huge benefits in time, efficiency and costs.

BY SCOTT OTTENS

skill level necessary to take material from a flat state to 3D formed parts. Many factors, such as tool selec- tion, bend-sequence devel- opment, material properties and machine capabilities must be considered. All of this requires operators of high intellectual capability to generate a machine pro- gram that will produce parts within specifications. Often, this lengthy setup proce- dure occurs at the machine, at the expense of perform- ing value-added work.

A Focus on Green-Light Time

To get a better understanding of the benefits possible with digital processing, consider a typical nine-step bending process, from setup through production:

1) Find materials—Locate material and part information, such as drawings and process instructions.

2) Tool/bend sequence and selec- tion—Specify the required tools for the job, and determine the sequence of bends.

3) Tool setup—Insert tooling into the machine.

4) Program creation—Enter bend

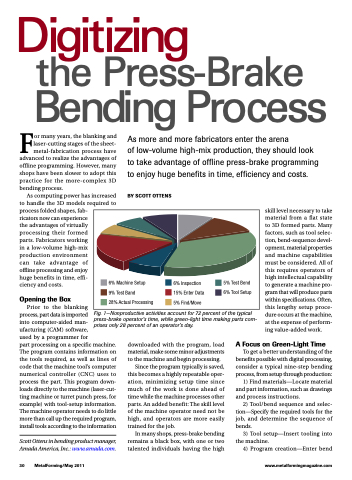

6% Machine Setup 9% Test Band

28% Actual Processing

6% Inspection 5% Test Bend 15% Enter Data 6% Tool Setup 5% Find/Move

Fig. 1—Nonproductive activities account for 72 percent of the typical press-brake operator’s time, while green-light time making parts com- prises only 28 percent of an operator’s day.

downloaded with the program, load material, make some minor adjustments to the machine and begin processing.

Since the program typically is saved, this becomes a highly repeatable oper- ation, minimizing setup time since much of the work is done ahead of time while the machine processes other parts. An added benefit: The skill level of the machine operator need not be high, and operators are more easily trained for the job.

In many shops, press-brake bending remains a black box, with one or two talented individuals having the high

30 MetalForming/May 2011

www.metalformingmagazine.com