Newer Automation Trend: Part Removal

Automated loading/unloading, along with the incorporation of material-storage towers, represent the most common laser and CNC punching machine automation found in fabricating operations, and time-tested ROI investigations have proven their worth. Next-level automation, on the other hand, remains less familiar, with ROI determination a trickier prospect.

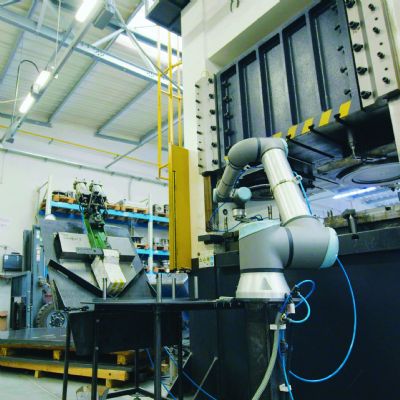

A next-level example, automated systems provide for part removal from sheet nests and subsequent stacking—a significant improvement over manual operations, according to Hillenbrand and Picardat.

“Robotic part picking of some sort automatically removes parts from the sheet skeleton, removing manual labor and simplifying the process of transferring parts to the next process,” Hillenbrand says. “Again, that doesn’t directly impact machine greenlight time and direct machine ROI, but it directly impacts part cost.”

Fabricators must scrutinize their operations when assessing the worth and payback of such systems.

“A fabricator may employ loading/unloading automation without part-separation automation,” explains Hillenbrand. “Shops running 24 hr. may run an unattended shift overnight. The machine is doing its work while the automation takes the finished parts and skeleton together and stacks them on, perhaps, a single offload pallet. The parts may move around a bit and intertwine with other parts and other skeletons. On the next shift, someone has to sort through that mess—5000 lb. of finished parts and skeletons stacked together like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Shop-floor personnel must separate the parts from the skeletons, a time-consuming task and, frankly, one that nobody wants to undertake. This menial task can be accomplished through part-removal automation, according to Picardat.

For its part, he offers, Amada provides two types of such automation, its PSR (Part Sorting Robot) and TK (TaKeout) systems.

“For larger laser-machine offerings, the PSR3015 system removes the entire sheet from the laser, with the laser continuing to cut the next sheet,” Picardat says. “The part-sorting robot grabs individual parts out of the skeleton and stacks them onto a pallet.”

Analysis provided by Amada helps verify the percentage of parts able to be separated and removed from the skeleton consistently, as well as the percentage possibly requiring removal with the skeleton.

The company provides TK (and PR, or Part Removal) systems for its solid-table machines, including CNC punching and combination units. This automation removes parts from the skeleton as soon as they are cut free, then stacks them in precise orientation on a pallet in the automation area. With part removal and stacking completed, the system transfers the skeleton to a separate pallet for disposal.

“With the PSR3015 and TK3015 systems,” says Picardat, “the robots grab individual cut parts and stack them precisely on the pallet―ready for transport to press brakes or any other process. This eliminates labor-intensive part removal and destacking, a difficult job that experiences high labor turnover. People really don't like busting out parts for 8 hr./day.”

AGVs, Automated Warehousing Team Up for Flexibility

Automated guided vehicles (AGVs) and automated warehousing also are making headway into fabricating operations, according to Picardat, with AGVs used primarily for material transport and reducing the need for forklifts.

“We’ve had some fabricators looking at AGVs to move stored blanks to press brakes as a means to reduce bottlenecks,” he says, citing an example where AGVs can prove effective. “Also, AGVs give a smaller shop the option to automate a certain area of its facility, and not make a huge capital investment across the entire factory. For example, in the past, automation had been considered as multiple core machines tied together and locked down into place. AGVs allow more versatility. You may have standalone press brakes here, bending robots over there, welding robots somewhere and more assembly and shipping equipment down the line. The AGVs can supply parts constantly to all of those operations for a relatively small cost.”

The use of AGVs ties directly to automation of warehousing operations. Picardat cites an automated-warehousing example: a customer looking to move parts into storage and keep track of those parts.

“Monthly, two employees at this shop sort through all of the parts that have been misplaced or left randomly throughout the plant,” he explains. “The goal is to sort and identify these parts, often made from expensive material, then store them for reuse. This fabricator sees the need for automated warehousing to transfer labor to more productive operations, and to better track and manage part locations.”

Warehouse-management systems can include tower systems stretching to hundreds of shelves, necessitating a large capital expense but providing a host of benefits.

“These systems can do many things,” offers Hillenbrand. “They can feed multiple machines from one centralized location, with finished parts returned to them and raw material fed to the laser cutting machines. A laser cuts the parts, a part-sorting unit stacks the parts on one pallet, while skeletons stack on another pallet, and those pallets return to the warehouse system. Then the press brake can call up and say, ‘send over those finished parts from the laser.’ The warehouse system feeds those parts to the brake for more work, and then those parts go back to the tower. The centralized storage system can be the hub for a factory’s entire work in progress.

“The challenge,” he continues, “involves space. The system can be designed into a new facility, but existing operations must find a way to shoehorn this automation in, change the workflow, and, yet, not disrupt current operations. In addition, shops may not want to place their faith in centralized automation. What if something fails in that system? they ask.”

AGVs provide cost-effective alternatives in these scenarios.

“They are less expensive and less intrusive,” Hillenbrand says. “AGVs may require a shop to clear out the aisles a bit, but don’t require a major overhaul of the shop layout and flow. Smaller material-storage racks can be placed throughout the facility, acting as buffer stations with AGVs transporting material and parts to and from the racks and machines—more flexible and more affordable, and taking up less space.”

While AGVs commonly find homes in operations overseas, in North America they’ve become quite noticeable in the medical industry and in warehousing operations such as those run by Amazon, for example, reports Picardat.

“We're seeing more interest on the sheet metal side because fabricators are becoming more comfortable with automation in general (think of multiple generations now quite familiar with smartphones),” he says. “I expect to see a big increase in AGV and automated warehousing automation on shop floors within the next five years.”

Much to Consider When Assessing ROI

Determining the value of automation must take into account the above-mentioned scenarios—a more-complicated task than simple ROI assessment for load/unload automation, but necessary to obtain an accurate picture of the automation payback. A fabricator should ask an automation supplier to provide guidance on ROI on various parameters and scenarios particular to their operations. For example, Amada, note Hillenbrand and Picardat, assesses various parameters from fabricators and has developed formulas to more accurately determine possible ROI from the common and next-level automation solutions explored here. MF

View Glossary of Metalforming Terms

See also: Amada North America, Inc

Technologies: CNC Punching, Cutting, Pressroom Automation

“Many shops look for simple, nonexpensive ways to move material on and off of the machines,” Hillebrand says, noting similar trends in purchases of CNC punching machines and combination systems. “The introduction of fiber laser cutting machines about 10 years saw a large increase in purchases of load/unload systems.”

“Many shops look for simple, nonexpensive ways to move material on and off of the machines,” Hillebrand says, noting similar trends in purchases of CNC punching machines and combination systems. “The introduction of fiber laser cutting machines about 10 years saw a large increase in purchases of load/unload systems.”

Webinar

Webinar